Water vendors are common in many parts of the world where water scarcity or lack of infrastructure limit access to drinking water, particularly in urban areas. Water vending refers to many forms of selling water: It ranges from individuals who carry water in containers on pushcarts, to water kiosks, where consumers fetch the water by themselves. In the literature, water vending usually refers to the formal or informal reselling or onward distribution of utility water, or water from other sources by small-scale vendors for domestic use (e.g. water kiosks, water carriers, tanker trucks, households reselling water from their utility water connections, etc.). This factsheet looks at how water-vending systems operate and discusses effects on health as well as effectiveness to reach the needs of the poor. The large-scale selling of industrialised packaged water, like bottled water, is discussed in another factsheet.

Vended water is common in many parts of the world where scarcity of supplies or lack of infrastructure limits access to suitable quantities of safe drinking water. Although water vending is more common in developing countries, it also occurs in developed countries (WHO 2011). Non-utility water vendors (henceforth simply referred to as water vendors) can provide an important service by filling this demand-supply gap. Both the quality and adequacy of supplies can vary (WHO 2011; KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006) (see also water and health and access to water and sanitation). Also, it is very common to find informal water vendors that are the only and primary way of reaching unserved areas as the image shown.

Adapted from KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN (2006)

Water vending can refer to many forms of sale of water: Water vending, the sale and distribution of water by the container, ranges from the delivery of water by tank trucks to the carrying of containers by individuals. The water may be obtained from private or municipal taps, stand posts, rivers or wells and sold either from a public vending station or door-to-door. Vendors may either sell water directly to consumers or act as middlemen, selling water to carriers who in turn serve the consumers” (ZAROFF & OKUN 1984). Three types of water vendors can be identified according to WHITTINGTON et al. (1989):

- Wholesale vendors: obtaining water from a source and selling it to distributing vendors.

- Distributing vendors – carters and carriers: obtaining water from a source or a wholesale vendor, and selling and delivering it to consumers door-to-door. Water carriers are typically male, and use some form of equipment in order to carry the heavy load of water. Plastic or metallic cans are loaded onto bicycles, hand-pushed, animal-drawn or mechanised carts or tanker trucks (see also human powered distribution and motorised distribution). Distributing vendors are typically poor people themselves, supplying to other low-income people.

Water vendor delivers water at Suakin using a donkey cart. Source: MAXINGOUT (n.y.) - Direct vendors – household resellers and standpipe operators:selling water to consumers coming to the source to purchase water, e.g. from water kiosks, standpipes, boreholes or household connections. In areas, where some households are connected to the network, and others not, water is typically obtained from neighbours. In many cities, connected households pay flat rates to the utility. Hence, the volumes sold to others will not affect the household’s monthly bill, and water reselling can be a lucrative business. Standpipe vendors have some form of contract and operate any stationary vending location, where water is provided to consumers, who then carry the water home (see also human powered distribution).

Water kiosk in Zambia. Source: GTZ (2009)

The most common type of private initiative in the water sector seems to be water vendors, including direct vendors or resellers as well as distributing vendors. It is difficult to say even roughly what share of the water market these vendors supply. But recent research indicates that water vendors provide an important service to reach the poor and areas that are difficult to develop with conventional infrastructure (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006). Another rapidly emerging business is that of pre-packaged or bottled water.

Water vendors of all kinds typically operate in areas where piped water is not forthcoming or accessible (see also the chapter availability and allocation (see PDF1 and PDF2). This is also where the urban poor most often live. Hence, there is a geographical overlap between urban poverty and water vending, even if the poorest of the poor may not be the most important clients (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006). Water vendors often operate as an extension of the piped system into undeveloped areas, and also supplant the piped system in areas where it is deteriorating. So they perform a parallel service by filling the demand-supply gap. If piped service were to expand rapidly, water vendors would be likely to go out of business (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006). In peri-urban areas, vendors typically transport the water for middle- and high-income households and sell it door-to-door, if they are not connected to the city mains (distributing vendors). Low-income households fetch water from standpipes or neighbours, which are connected to the mains (direct vendors) (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006).

Formal or informal small-scale suppliers may undertake water vending. The term “informal” refers to all types of water suppliers who are not operating in the legal framework of water management in a given area (ANGUELTOU-MARTEAU 2008) (see also policies and legal framework). Where formal vending is practised, the water typically comes from treated utility supplies or registered sources and is supplied in tankers, or directly caught by customers from standpipes or water kiosks. In contrast, informal suppliers tend to use a range of source, including untreated surface water sources, dug wells and boreholes (see also manual pumping and mechanised pumping), and deliver small volumes for domestic use (WHO 2011) (see also human powered distribution and motorised distribution).

Adapted from WHO (2011) and KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN (2006)

With regard to water quality, water vendors are often blamed for supplying unsafe water (see also water quality testing). Enforcement of regulation and monitoring is very difficult, especially for decentralised and informal packaging (see also strengthening enforcement bodies for water sources and creating policies and a legal framework for water sources). Further, it is quite likely that all the pouring from one vessel to another exacerbates the risk of contamination at the point of retail or at the household level(see also HWTS, safe storage, water quality testing, pathogens and contaminants). Still, a study covering several places in East Africa found water from vendors and kiosks as well as from household connections to be relatively safe in terms of low diarrhoea prevalence among children (TUMWINE et al. 2002).

Sources used by vendors include tap water from standpipes and other outlets or untreated surface water sources, dug wells and boreholes (see also manual pumping and mechanised pumping). Surface water and some dug well and borehole waters are not suitable for drinking unless subject to treatment (see also chlorination, WATASOL, point of use water treatment (see PPT), awareness raising in water purification (see PPT), and health and hygiene issues).

Adapted from KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN (2006)

Normally water vending is a competitive business. The level and harshness of competition in water markets may vary, but the earlier stereotypes of water vendors being highly exploitative in the prices they charge has been replaced with a recognition that the prices charged generally reflect real costs (UN-HABITAT 2003). The competitiveness usually occurs because there are many people without jobs and entry into the vendor market is easy. However, achieving profitability in the vendor market is more difficult. As the vendors must win their customer’s loyalty and maintain their equipment on a daily basis, they must be ready to innovate and adapt in order to stay in business in this competitive market (COLLIGNON & VEZINA 2000). But there are also cases, where the poorest are faced with a high dependence on vendors, making vending a lucrative business, e.g. in Jakarta (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006) (see also access to water and sanitation).

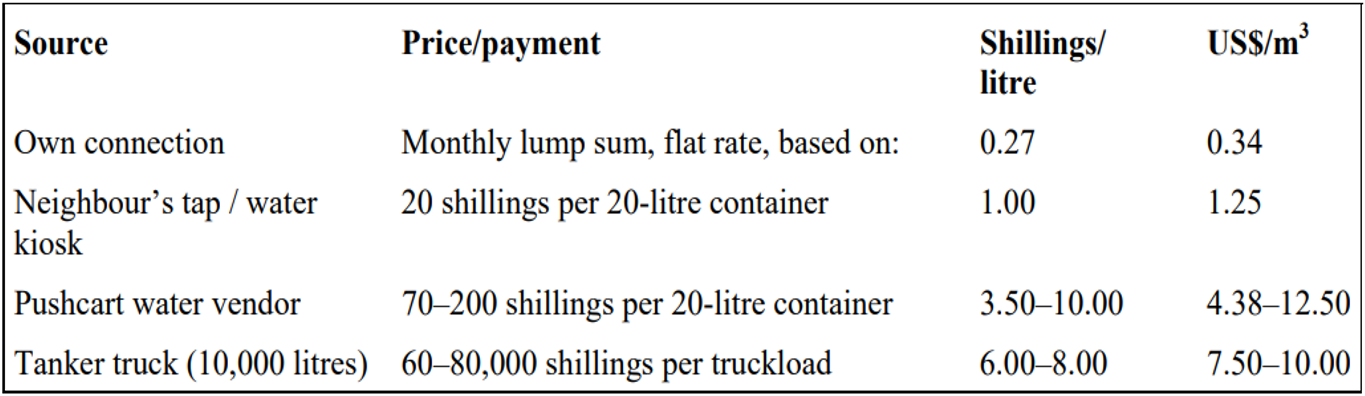

In any case, vended water is always more expensive than a house connection, if available, or public taps. But vendor systems often appear to be more robust than piped systems in developing countries. The example of water prices in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, where many dwellers rely on out-of-pipe water supply, shows that water from a water vendor will cost around 10 to 40 times more than from an own connection, depending on the conditions of supply and the location of the consumer. However, water vended at water kiosks only costs four times more than from an own connection (see graph).

Water vendors typically operate outside or at the margins of established legal frameworks (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006). They are often actively discouraged, i.e. ignored or suppressed. However, most utilities choose not to punish reselling households, as water vendors are the symptom, not the cause, of insufficient water provision (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006).

Regulation of distributing vendors is difficult: partly due to their great number and mobility, and partly due to the low level of earning. Taxation or licences may drive up water prices or extract dues rather than bringing in tax revenue or improve basic hygiene. If selling water is illegal or if standards are set too high, the net result will often be smaller quantities of water being made available at an even lower standard on what amounts to a black market (see also water pricing in general) (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006).

With respect to quality control, where formal systems exist, the priority is likely to be to increase access to formal water supplies or promote household water treatment rather than controlling vended water quality (see also point of use water treatment (see PPT), awareness raising in water purification (see PPT), access to water and sanitation and water and economics) (WHO 2011).

A major problem for consumers is the high price of water on many informal water markets. Regulating the price charged is rarely an option as control is difficult. However, it may be possible to remove constraints that drive vendor prices up. E.g. punishing water vendors where no other option of water supply exists only keeps prices high. This implies the development of an enabling business environment, e.g. changing counterproductive laws against water vending and facilitate their access to financial resources (see also creating an enabling environment for water sources, Public Private Partnerships, government contributions, subsidies, microfinance and cost sharing (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006).

Adapted from KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN (2006)

According to the official target of the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs), improvement is achieved when people switch from water vendors or unimproved sources to piped-water connections or free public standpipes within a kilometre of their home (see also access to water and sanitation). But by suppressing water vending, there is the danger of authorities making obtaining water for deprived residents even more difficult. A negative attitude towards water vending reduces the available water supply and hurts the deprived residents by driving prices up still further. Their ability to reach the poor and improving water supplies in areas that are difficult to develop with conventional infrastructure are important services (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006).

On the other hand, assuming that water vending is desirable per se is also problematic. Given the high vendor prices, many low-income households cannot purchase sufficient amounts of water to meet their hygiene needs (see also the right to water and sanitation). The challenge is to improve currently inadequate water and sanitation services, through the most effective means available, including water vendors where appropriate (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006) (see also point of use water treatment (see PPT), semi centralised drinking water treatments, EMPOWERS approach, water safety plans, linking up water management and agriculture, SSWM concept introduction).

There is nothing contradictory about a water strategy that aims at getting vendors to provide improved water (and sanitation) services to the urban poor in the short run, and to drive vendors out of business by way of providing better utility services in the long run (KJELLEN & MCGRANAHAN 2006). An obvious option for expanding water coverage would be to further explore the existing distribution mechanisms of resale of house connection water (KEENER et al. 2010) (see also exploring tools).

- Short-time solution in growing urban and peri-urban areas

- Possible partnerships between utilities and small-scale providers

Water Vendor in Nigeria

Informal Water Suppliers Meeting Water Needs in the Pero-Urban Territories of Mumbai, an Indian Perspective

This paper addresses the issue of informal water providers in the peri-urban areas of Mumbai. The paper examines whether we are heading towards new forms of urban governance, where informal actors no longer compete with each other, but cooperate with public utilities and emerge as an extension of the public utility.

ANGUELTOU-MARTEAU, A. (2008): Informal Water Suppliers Meeting Water Needs in the Pero-Urban Territories of Mumbai, an Indian Perspective. Grenoble: Université de Grenoble URL [Visita: 30.11.2012]Independent Water and Sanitation Providers in African Cities. Full Report of a Ten-Country Study

This ten-country study in Africa, provides a wealth of information on a vibrant independent water and sanitation sector that responds to market niches and meets the needs of both the poor and other unserviced communities on a very broad scale. The countries covered were Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Uganda, Senegal, and Tanzania. The overall picture that emerges from the study suggests that by recognizing and regularizing the activities, roles, and institutional position of independent providers, and by facilitating intermediation, coordination, and partnership between city-wide operators and independent providers, municipal and national authorities can set the stage for better delivery of water and sanitation services to the urban poor.

COLLIGNON, B. VEZINA, M. (2000): Independent Water and Sanitation Providers in African Cities. Full Report of a Ten-Country Study. Washington, DC: UNDP-World Bankd Water and Sanitation Program URL [Visita: 30.11.2012]Nairobi’s informal water vendors: heroes or villains?

Case Study: Water Kiosks. How the combination of low-cost technology, pro-poor financing and regulation leads to the scaling up of water supply service provision to the poor

Water kiosks are a low-cost technology to scale up the water supply to the poor. The approach taken typically includes the decentralisation and commercialisation of water supply and sanitation (WSS) services, taking into account the needs of the poor in particular. This report gives an introduction to the water kiosk concept, its impact and challenges, and an example of a best practice implementation: the case of Zambia.

GTZ (2009): Case Study: Water Kiosks. How the combination of low-cost technology, pro-poor financing and regulation leads to the scaling up of water supply service provision to the poor. Eschborn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH. [Accessed: 22.03.2019] PDFProvision of Water to the Poor in Africa. Experience with Water Standposts and the Informal Water Sector

This paper reviews recent literature and available data on standpipes and the informal water sector in Sub-Saharan Africa. It identifies gaps in the research and outlines recommendations for additional research on water provision for the poor.

KEENER, S., LUENGO, M. and BANERJEE, S. (2010): Provision of Water to the Poor in Africa. Experience with Water Standposts and the Informal Water Sector. Washington, DC: The World Bank URL [Visita: 22.03.2019] PDFInformal Water Vendors And The Urban Poor

This working paper looks at how water-vending systems operate, how effective they are in meeting the needs of the urban poor, and how this effectiveness might be improved. The paper concentrates on the small-scale and informal vendors, most of whom work independently with very little capital. Nevertheless, they display enormous diversity and flexibility, and are adept at responding to the needs of all but the very poorest households.

KJELLEN, M and MCGRANAHAN, G. (2006): Informal Water Vendors And The Urban Poor. (= Human Settlements Discussion Paper Series ). London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) URL [Visita: 30.11.2012] PDFWater vendor delivers water at Suakin using a donkey cart

Diarrhoea and Effects of Different Water Sources, Sanitation and Hygiene Behaviour in East Africa

Water and Sanitation in the World’s Cities. Local Action for Global Goals

Water Vending Activities in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Ukunda, Kenya

Vended Water. Chapter 6.1

Customers and Providers

Water Vending in Developing Countries

Informal Water Vendors And The Urban Poor

This working paper looks at how water-vending systems operate, how effective they are in meeting the needs of the urban poor, and how this effectiveness might be improved. The paper concentrates on the small-scale and informal vendors, most of whom work independently with very little capital. Nevertheless, they display enormous diversity and flexibility, and are adept at responding to the needs of all but the very poorest households.

KJELLEN, M and MCGRANAHAN, G. (2006): Informal Water Vendors And The Urban Poor. (= Human Settlements Discussion Paper Series ). London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) URL [Visita: 30.11.2012] PDFIndependent Water and Sanitation Providers in African Cities. Full Report of a Ten-Country Study

This ten-country study in Africa, provides a wealth of information on a vibrant independent water and sanitation sector that responds to market niches and meets the needs of both the poor and other unserviced communities on a very broad scale. The countries covered were Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Uganda, Senegal, and Tanzania. The overall picture that emerges from the study suggests that by recognizing and regularizing the activities, roles, and institutional position of independent providers, and by facilitating intermediation, coordination, and partnership between city-wide operators and independent providers, municipal and national authorities can set the stage for better delivery of water and sanitation services to the urban poor.

COLLIGNON, B. VEZINA, M. (2000): Independent Water and Sanitation Providers in African Cities. Full Report of a Ten-Country Study. Washington, DC: UNDP-World Bankd Water and Sanitation Program URL [Visita: 30.11.2012]Case Study: Water Kiosks. How the combination of low-cost technology, pro-poor financing and regulation leads to the scaling up of water supply service provision to the poor

Water kiosks are a low-cost technology to scale up the water supply to the poor. The approach taken typically includes the decentralisation and commercialisation of water supply and sanitation (WSS) services, taking into account the needs of the poor in particular. This report gives an introduction to the water kiosk concept, its impact and challenges, and an example of a best practice implementation: the case of Zambia.

GTZ (2009): Case Study: Water Kiosks. How the combination of low-cost technology, pro-poor financing and regulation leads to the scaling up of water supply service provision to the poor. Eschborn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH. [Accessed: 22.03.2019] PDFProvision of Water to the Poor in Africa. Experience with Water Standposts and the Informal Water Sector

This paper reviews recent literature and available data on standpipes and the informal water sector in Sub-Saharan Africa. It identifies gaps in the research and outlines recommendations for additional research on water provision for the poor.

KEENER, S., LUENGO, M. and BANERJEE, S. (2010): Provision of Water to the Poor in Africa. Experience with Water Standposts and the Informal Water Sector. Washington, DC: The World Bank URL [Visita: 22.03.2019] PDFInformal Water Suppliers Meeting Water Needs in the Pero-Urban Territories of Mumbai, an Indian Perspective

This paper addresses the issue of informal water providers in the peri-urban areas of Mumbai. The paper examines whether we are heading towards new forms of urban governance, where informal actors no longer compete with each other, but cooperate with public utilities and emerge as an extension of the public utility.

ANGUELTOU-MARTEAU, A. (2008): Informal Water Suppliers Meeting Water Needs in the Pero-Urban Territories of Mumbai, an Indian Perspective. Grenoble: Université de Grenoble URL [Visita: 30.11.2012]Water Vending in Nigeria. A Case Study of Festac Town, Lagos, Nigeria

Festac Town, Lagos, Nigeria is a typical community that is presently not being serviced by water utilities. Households therefore seek other alternative sources including water vending. This paper examined the role of water vending in household water supply delivery in this community. It identified the sources of water supply by the vendors, assessed their level of patronage among households and identified the problems associated with their operations. The paper concludes that the most sustainable strategy would be to resuscitate the moribund piped water supply system earlier initiated by the Water Supply Agency (WSA).

OLAJUYJUGBE, A.E. ; ROTOWA, A.E. ; ADEWUMI, I.J. (2012): Water Vending in Nigeria. A Case Study of Festac Town, Lagos, Nigeria. Entradas: Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences: Volume 3 , 1. URL [Visita: 09.07.2019]Case Study: Water Kiosks. How the combination of low-cost technology, pro-poor financing and regulation leads to the scaling up of water supply service provision to the poor

Water kiosks are a low-cost technology to scale up the water supply to the poor. The approach taken typically includes the decentralisation and commercialisation of water supply and sanitation (WSS) services, taking into account the needs of the poor in particular. This report gives an introduction to the water kiosk concept, its impact and challenges, and an example of a best practice implementation: the case of Zambia.

GTZ (2009): Case Study: Water Kiosks. How the combination of low-cost technology, pro-poor financing and regulation leads to the scaling up of water supply service provision to the poor. Eschborn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH. [Accessed: 22.03.2019] PDFInformal Water Vendors and Service Providers in Uganda: The Ground Reality

This paper is a beginning or a starting point for further research informal water vending in Uganda and highlights issues for further research, discussion and policy formulation. The paper is based almost entirely on primary information around Kampala and several small towns. More than 20 localities, mostly slums, informal settlements and poorer sections of Kampala were visited in order to find out how and from where people obtained water and the price they paid for it. Discussions were held directly with consumers, vendors, government authorities, and NGOs.

PANGARE, G. PANGARE, V. (2008): Informal Water Vendors and Service Providers in Uganda: The Ground Reality. Bonn: The Water Dialogues. [Accessed: 04.12.2012] PDFEnvironmental Factsheet. Independent Water Entrepreneurs in Latin America

This report outlines the findings of the six-country study (Paraguay, Argentina, Colombia, Guatemala, Peru and Bolivia) of small-scale providers of water supply and sanitation service in Latin America carried out by the Water and Sanitation Program.

SOLO (2003): Environmental Factsheet. Independent Water Entrepreneurs in Latin America. Washington DC: The World Bank URL [Visita: 17.05.2019]Services and Supply Chains: The Role of the Domestic Private Sector in Water Service Delivery in Tanzania

This report presents findings from a review of the service activities of informal private water vendors in Dar es Salaam. Tanzania’s capital is a rapidly growing city, and around 70 percent of the population lacks proper housing and lives in informal settlements. Large parts of the city remain unserved by the water utility and many of those who have access to the piped network suffer from intermittent supply. As a result, small-scale private water vendors provide an essential service for many, in particular low-income households in the city that would not otherwise be served. Yet, the overall result is an extremely costly service, which heavily penalizes low-income households.

UNDP (2011): Services and Supply Chains: The Role of the Domestic Private Sector in Water Service Delivery in Tanzania. New York: United Nations Development Programme URL [Visita: 04.12.2012]Small-Scale Water Providers in Kenya: Pioneers or Predators?

In Kenya small-scale private water providers have entered the market to fill the gap left in public service provision. This study examines what role they play in ensuring affordable, safe and reliable water supply. It finds that small-scale providers increase water supply coverage and reduce time poverty. However, low-income households pay high prices for water of questionable quality.

UNDP (2011): Small-Scale Water Providers in Kenya: Pioneers or Predators? . New York: United Nations Development Programme URL [Visita: 30.11.2012]The Experience of Small-Scale Water Providers in Serving the Poor in Metro Manila

Small-scale water providers continue to supply water to many parts of Metro Manila, the Philippines. The study found that a high proportion of the poor rely on water services supplied by small-scale water providers, but that these households pay a higher unit rate for the water than their more affluent neighbours. The study yields a number of recommendations, including rationalizing the price of water for poor customers, improving service efficiencies to reduce the costs of supplying water, and developing collaborative relationships among the government regulator, utility, and small-scale water providers.

WSP (2004): The Experience of Small-Scale Water Providers in Serving the Poor in Metro Manila. Washington, D.C.: The Water and Sanitation Programme of the World Bank Group URL [Visita: 09.07.2019]Get to Scale in Urban Sanitation!

Taking urban sanitation to scale requires ‘scaling out’ models that work for poorer communities, and at the same time ‘scaling up’ sustainable management processes. This short note reports scale-out and scale-up experience from Maputo and Antananarivo.

WSUP (2013): Get to Scale in Urban Sanitation!. (= Practice Note , 10 ). London: Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor (WSUP) URL [Visita: 22.04.2019]Water Kiosks. Bringing sustainable water supply and sanitation to the urban poor

This flyer shows the benefits of water kiosks at a glance, as well as their design elements, management concept and impact.

GTZ (2009): Water Kiosks. Bringing sustainable water supply and sanitation to the urban poor. Eschborn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH PDFSmall-Scale Water & Sanitation

Here you find more material about the private sector participation of small-scale water providers, particularly in Africa.

The Lives of Jakarta's Street Vendors - Hasanuddin, Water Seller

The film “The Lives of Jakarta's Street Vendors - Hasanuddin, Water Seller” is a short portrait of the water vendor Hasanuddin. It gives an insight into the water vending system in Jakarta.