Today’s water and sanitation crisis is rather an issue of access than of scarcity. It is mainly rooted in poverty, power and inequality, not in physical availability (UNDP 2010). More people in the world own cell phones than have access to a toilet. And as cities and slums grow at increasing rates, the situation worsens. Every day, lack of access to clean water and sanitation kills thousands, leaving others with reduced quality of life (WATER.ORG 2011).

Only two out of five people have access to safe sanitation services; and around seven in ten have access to safe drinking water service (WHO & UNICEF 2017). Over 340,000 under five children die from diarrhoeal diseases yearly because of poor sanitation and hygiene as well as unsafe drinking water (WHO & UNICEF 2015).

Access to water and sanitation refers not only to its quantity but also to its quality. How far the quality and especially the functionality are considered to evaluate the access is a controversial question (see below).

Considering that the growing world population together with climatic changes might worsen the water scarcity for some regions, the promotion of access to water and sanitation is a steadily increasing challenge.

Water is needed for all aspects of life. Without safe drinking water, humans, animals and plants cannot survive. And still, half of the people in the developing world are suffering from diseases associated with inadequate provision of water supply and sanitation facilities (see also water sanitation and health). Every day around 1000 children die from diarrhoea (see also water-related diseases). Further, 443 million school days are lost annually worldwide due to diarrhoeal diseases (WATERAID.ORG 2011). Statistics from 2016 shows that 190 million people live under the risk of trachoma blindness, which is associated with lack of safe water for washing face and hands (WHO N.D.). Furthermore, inadequate sanitation causes economic losses (WSP 2010) and access to imoproved saitation is seen to be one of the most important development drivers (UNDP 2010).

Access to water and sanitation, the prevention of polluting water, and improved hygiene are essential in improving the living standards of anyone on this planet. Furthermore, adequate water resources are essential for food production and thus for proper nutrition.

In December 2015, the the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable development was launched as a result of meetings between World Leaders in September of the same year. . The new agenda calls for achieving the new 17 Sustainable Development Goals within the next 15 years for all people and countries. The SDGs came in as an improvement for the MDGs, which didn’t cover all aspects of the holistic development approach. While the MDGs covered only eight issues (mainly poverty and hunger, primary education, gender equality and women empowerment, child mortality, maternal health, combat diseases, environmental sustainability and global partnership for development), the SDGs are more far comprehensive and thorough.

At the headquarters of the United Nations, members from different countries worked together to set the new 17 Sustainable Development Goals to combat poverty and hunger as well as promote for good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, access to clean water and sanitation and affordable clean energy. The SDGs also covered topics related to economic growth, sustainable consumption and production, life below water, climate action, life on land, sustainable cities and communities (UN 2015).

The SDG 6 aims to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. The goal includes six targets that give a normative framework and direction for development efforts in water and sanitation (ERLMANN ET AL 2017). Water is at the heart of the 2030 Agenda as it is a key prerequisite for overall SDG achievement. As interventions in water and sanitation contributes to improvements towards other goals like health, poverty, food security, it makes sense using the water and sanitation system of a region as an entry point to tackling the 2030 Agenda. Likewise, working on other goals like education and governance can leverage interventions in water and sanitation.

The SDG indicators related to water, sanitation and hygiene are far more extensive. While the MDGs had only one target related to water and sanitation, the SDGs had one goal with different indicators (SDG 6) as well as indicators from other goals: SDG 3 targeting health related issues, SDG 11 aimed at promoting sustainable cities and communities, SDG 12 on the topic on responsible consumption and production and SDG 15 focusing on the protection of land and water ecosystems. This indicates the critical importance of water and its links to the different aspects of sustainable development. It also emphasises the interlinkages between the different goals and the improved impacts in the process of achieving them. Moreover, the (water-related) SDGs are targeting all world population, while the only water –related MDG target (7c) aimed to halve the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation (ERLMANN ET AL 2017). In spite of its increasing importance, hygiene was not explicitly included in the MDGs. Furthermore, having more detailed SDGs ensures better data collection and analysis to fulfil the SDGs. By this transition, more attention has been brought worldwide to the topic of water security.

In order to measure the implementation progress of SDG 6, six outcome targets (6.1-6) were introduced and two MoI (means of implementation) targets; 6.a and 6.b. Each of the MoI targets applies to the outcome targets as well as the overall goal. The targets are as follows:

• 6.1 By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all,

• 6.2 By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations

• 6.3 By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally,

• 6.4 By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity,

• 6.5 By 2030, implement integrated water resources management (IWRM) at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate,

• 6.6 By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands rivers, aquifers and lakes.

• 6.a By 2030, expand international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries in water- and sanitation-related activities and programmes, including water harvesting, desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling and reuse technologies.

• 6.b Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management (https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg6).

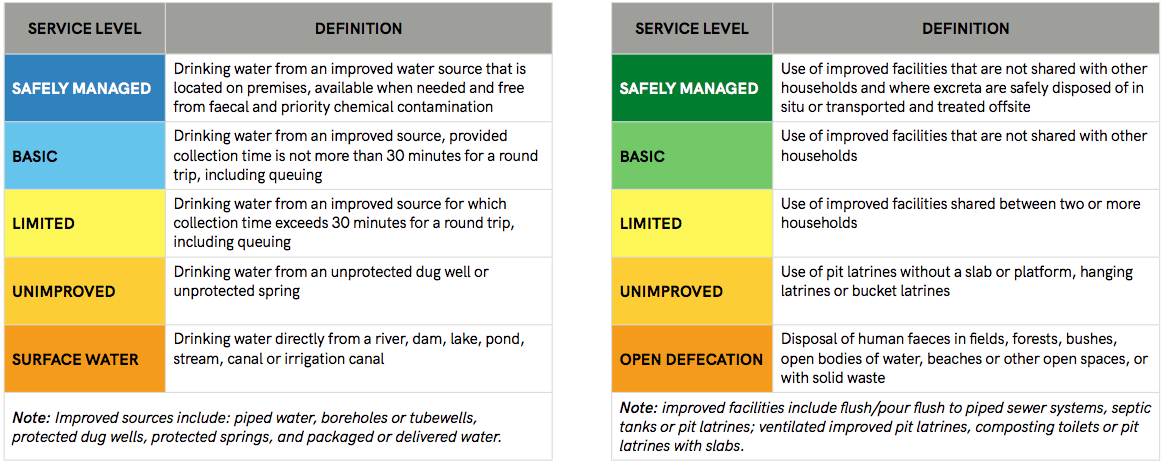

Because definitions of improved sanitation facilities and drinking-water sources can vary widely within and among countries and regions, and because progress has to be measured at global level and across time, the Joint Monitoring Programme on Water and Sanitation (JMP) has defined by categories explaining what improved and what unimproved water sources and sanitation facilities on the different levels mean. These categorises also allow for enhanced monitoring of the targets (WHO & UNICEF 2017).

To categorise different sanitation and hygiene facilities as well as drinking-water sources is the only way to measure access to water and sanitation globally and over time. This is the categorisation introduced and used by the JMP. Source: WHO & UNICEF (2017)

In line with the SDG indicator definition which stipulates “safely managed” as a proxy for “access to improved facilities”, the JMP measures and reports on the actual use of improved facilities. The household surveys on which the JMP relies also measure “use” and not “access”–since access involves many additional criteria other than use (AMCOW 2010).

Although the SDGs have filled the gaps that were present in the MDGs and specifically in relation to water (i.e.: inequalities to water access), some of the outcome and MoI targets have been framed inconsistently, where MoI targets are in some cases more of an outcome target rather than an MoI. On the contrary, target 6.5 ‘by 2030, implement integrated water resources management (IWRM) at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate’ is read more as a management approach and thus a MoI.

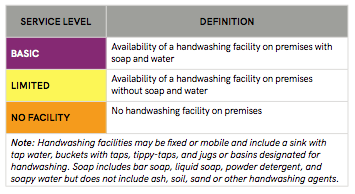

In 2015, about 89 % of the world population (6.5 billion people) had access to improved sources of drinking water that needed less than 30 minutes per trip to be collected, these people have been categorised as having at least a basic drinking water service. The proportion of people with at least a basic drinking service has grown by an average of 0.49 % per year during the MDG period between 2000 and 2015 (UNICEF & WHO 2017).

Percentage of population with at least and limited drinking water services in the different world regions (UNICEF & WHO 2017)

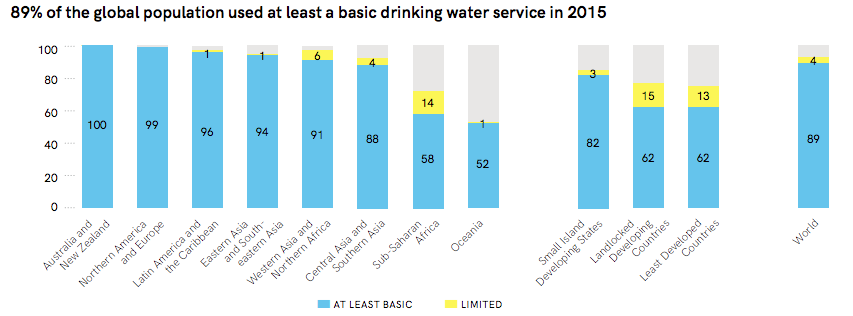

Worldwide use of improved drinking-water sources in 2015. Source: UNICEF WHO (2017)

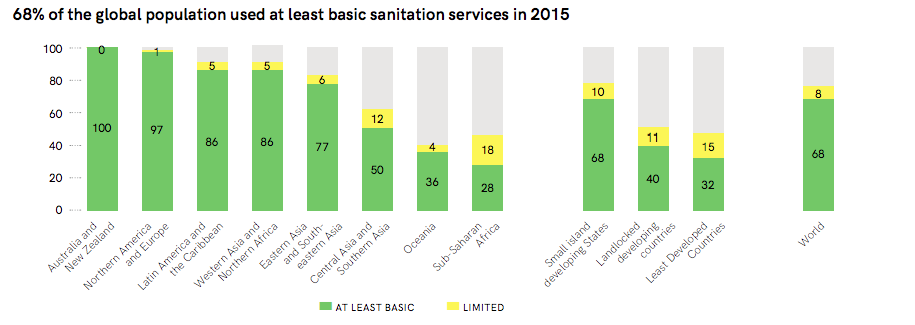

In 2015, improved sanitation facilities are used by only 68 % of the world population. Progress in sanitation has been lower than it has been for water, in the meantime basic sanitation is decreasing in 20 countries. The 2.3 billion people in the world who do not use improved sanitation facilities rely on open defecation or the use on unimproved facilities. Out of the 24 countries, where at least one person in five has limited sanitation services, 16 are located in sub-Saharan Africa (UNICEF & WHO 2017).

The global picture masks great disparities between regions: while virtually the entire population of the developed regions uses improved facilities, in developing regions only around half the population uses improved sanitation (UNICEF & WHO 2012).

Percentage of population with at least basic and limited sanitation services in the different world regions (UNICEF & WHO 2017)

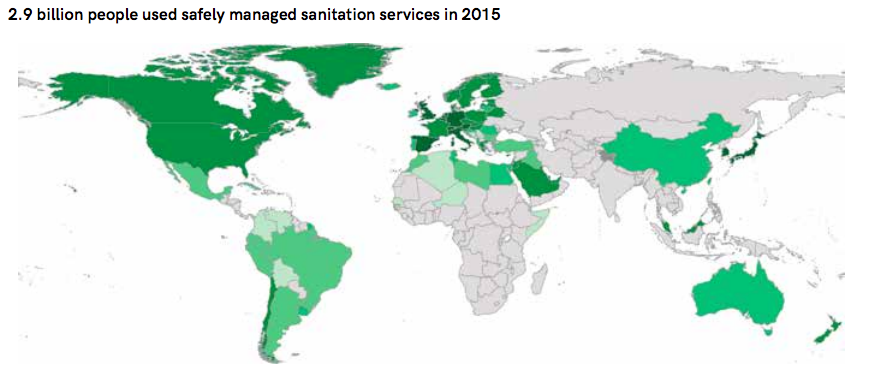

Worldwide use of improved sanitation facilities in 2015, putting highlights on the urgency of sanitation improvements in Southern Asia, Sub-Saharan and Central Africa. Source: UNICEF & WHO (2017)

A lot of progress has happened between 2000 and 2015 in sanitation and sanitation practices. However, the progress is slow and needs to double in order to reach the target of eliminating open defecation in rural areas by 2030. This can be noted from the percentage of people practising open defecation between 2000-2015: 20% to 12%(UNICEF & WHO 2017).

While hygiene was not included in the MDGs, the SDGs had a target for it: ‘proportion of population with handwashing facilities with soap and water at home.

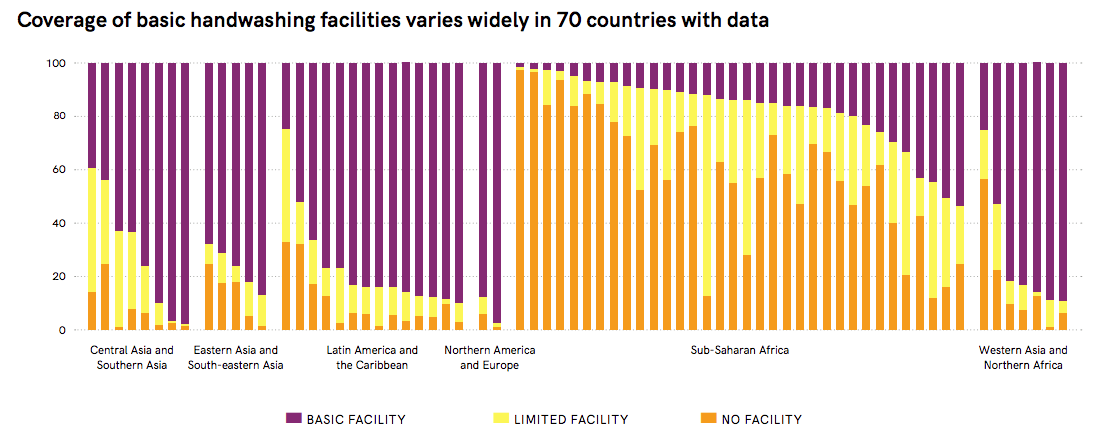

Proportion of population with basic and limited handwashing facilities in 70 countries with data in the different world regions (UNICEF & WHO 2017)

Proportion of population with basic and limited handwashing facilities in 70 countries with data in the different world regions (UNICEF & WHO 2017)

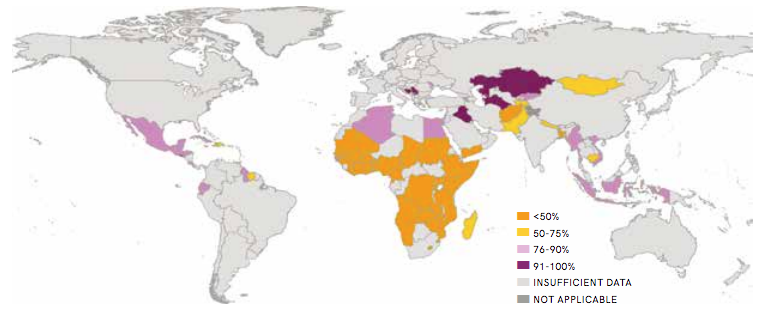

In 2015, 15% of sub-Saharan Africa had access to handwashing facilities, while 76% of Western Asia and northern Africa had access. Moreover, availability of handwashing facilities has always been higher in urban than in rural areas in each of these regions. In developed countries, there is no sufficient data to generate estimates (see map of hygiene coverage in the world in 2015).

Proportion of population with handwashing facilities including soap and water at home in 2015 (UNICEF & WHO 2017)

Although taboos topics such as defecation and menstrual hygiene have been broken and behavioural change has been mentioned and even examined in the water and sanitation sector generally and in relation to hygiene specifically, much remains to be done. Hygiene promotion should consider marginalised people and children as well as be kept on the agenda in times of instabilities and crisis (UNICEF 2016). Out of the 52 countries who reported WASH expenditures, only six countries with population of 204 million people have spent US$ 63 million (US$ 0.31 per capita) on hygiene promotion (GLAAS 2017).

Regarding to water and sanitation, the shift from the MDGs to SDGs has changed the perspective and importance on water and sanitation topics in the world. While MDGs where focusing on access of water and basic sanitation, the new SDG 6 and other targets related to water are far more comprehensive. This emphasises the need for better management, capacity and resources management as well as support (UN-WATER, N.D.).

In 2015, 5.2 billion people had access to safely managed drinking water and 2.9 billion had access to safely managed sanitation service. The progress in access to water is faster than in access to sanitation, and the gap between rural and urban safe water supply is still substantial in some regions. As hygiene has only been included in SDGs and not in the MDGs, its progress is the slowest among the three (water, sanitation and hygiene) and sufficient data is even not available.

Continued efforts are needed to reduce urban-rural disparities and inequities associated with poverty; to dramatically increase coverage in countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania; to promote global monitoring of drinking water quality; to bring sanitation coverage ‘on track’. With half the population of developing regions without safely managed sanitation, the 2030 target appears to be hard to reach. But the SDGs are still attainable.

SDG 6 along the water and nutrient cycles

This AGUASAN publication illustrates how the water and nutrient cycles can be used as a tool for creating a common understanding of a water and sanitation system and aligning it with SDG 6.

BROGAN, J., ERLMANN, T., MUELLER, K. and SOROKOVSKYI, V. (2017): SDG 6 along the water and nutrient cycles. Using the water and nutrient cycles as a tool for creating a common understanding of a water and sanitation system - including workshop material. Bern (Switzerland): AGUASAN and Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) URL [Visita: 26.03.2019] PDFProgress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Update and SDG Baselines 2017

This document provides an overview on all related updates for SDG 6 until its issue date.

WHO UNICEF (2017): Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Update and SDG Baselines 2017. Geneva: PDFProgress on Sanitation and Drinking-Water. 2015 Update

This well illustrated report describes the status and trends with respect to the use of safe drinking-water and basic sanitation, and progress made within the framework of the MDG drinking-water and sanitation target. As the MDG era comes to a close, this report shows how far we have come. For example, in a major global achievement, the target for safe drinking water was met in 2010, well ahead of the MDG deadline of 2015. Over 90 per cent of the world’s population now has access to improved sources of drinking water. At the same time, the report highlights how far we still have to go. The world has fallen short on the sanitation target, leaving 2.4 billion without access to improved sanitation facilities. Each JMP report assesses the situation and trends anew and so this JMP report supersedes previous reports (e.g. from 2012, 2013 and 2014).

WHO ; UNICEF (2015): Progress on Sanitation and Drinking-Water. 2015 Update. Geneva: World Health Organisation (WHO) / New York: UNICEF URL [Visita: 07.07.2015]Progress on Drinking Water and Sanitation

There are still 780 million people without access to an improved drinking water source. And even though 1.8 billion people have gained access to improved sanitation since 1990, the world remains off track for the sanitation target. It is essential to accelerate progress in the remaining time before the MDG deadline, and I commend those who are participating in the Sustainable Sanitation: Five Year Drive to 2015. This report outlines the challenges that remain. Some regions, particularly sub- Saharan Africa, are lagging behind. Many rural dwellers and the poor often miss out on improvements to drinking water and sanitation. And the burden of poor water supply falls most heavily on girls and women. Reducing these disparities must be a priority.

UNICEF ; WHO (2012): Progress on Drinking Water and Sanitation. Update 2012. New York/Geneva: United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF)/World Health Organisation (WHO) URL [Visita: 19.04.2012]The Sanitation Ladder – A Need for a Revamp?

GOAL WaSH Programme: Country Sector Assessments Volume 2. Governance, Advocacy and Leadership for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

A Snapshot of Drinking Water and Sanitation in Africa – 2010 Update. A Regional Perspective Based on New Data from the WHO/UNICEF JMP for Water Supply and Sanitation

This Snapshot of Drinking Water and Sanitation in Africa (2010 update) aims at informing on the status and trends in progress towards achieving the MDG drinking-water and sanitation target in Africa. It includes statistics, illustrations, tables and graphics specifically related to the African continent, based on the JMP 2010 report data and prepared in collaboration with the WHO/UNICEF JMP.

AFRICAN MINISTERS’ COUNCIL ON WATER (AMCOW) (2010): A Snapshot of Drinking Water and Sanitation in Africa – 2010 Update. A Regional Perspective Based on New Data from the WHO/UNICEF JMP for Water Supply and Sanitation. Abuja: African Ministers’ Council on Water URL [Visita: 16.05.2019]The Economic Impacts of Inadequate Sanitation in India

Inadequate sanitation causes India considerable economic losses, equivalent to 6.4 percent of India’s GDP in 2006 at US$53.8 billion, according to The Economic Impacts of Inadequate Sanitation in India, a new report from the Water and Sanitation Program (WSP). The study analysed the evidence on the adverse economic impacts of inadequate sanitation, which include costs associated with death and disease, accessing and treating water, and losses in education, productivity, time, and tourism. The findings are based on 2006 figures, although a similar magnitude of losses is likely in later years.

WSP (n.y): The Economic Impacts of Inadequate Sanitation in India. New Delhi: Water and Sanitation Program (WSP), World Bank URL [Visita: 29.03.2011]Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015

The general assembly adopts the following outcome document of the United Nations summit for the adoption of the post-2015 development agenda

UN (2015): Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 . URL [Visita: 07.06.2018]Launch of new sustainable development agenda to guide development actions for the next 15 years

This links provides an article about the lunching of the SDGs

https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?page=view&nr=1021&type=230&menu=2059 [Visita: 06.06.2018]Global Health Observatory (GHO) data

This links provides information on one of the major diseases caused by low quality hygiene.

http://www.who.int/gho/neglected_diseases/trachoma/en/ [Visita: 06.06.2018]What Does It Take to Scale Up Rural Sanitation?

This working paper addresses lessons and best practices that were identified by the Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) to generate demand and supply for sanitation on the local and household level as well as strengthening governments in order to scale up sanitation projects.

PEREZ, E. CARDOSI, J. COOMBES, Y. DEVINE, J. GROSSMAN, A. KULLMANN, C. KUMAR, C.A. MUKHERJEE, N. PRAKASH, M. ROBIARTO, A. SETIWAN, D. SINGH, U. WARTONO, D. WSP (2012): What Does It Take to Scale Up Rural Sanitation?. (= Scaling Up Rural Sanitation ). Water and Sanitation Program (WSP)Toilets for health

This is a comprehensive report on why toilets matter. The report is rich in infographics, provides overview of the sanitation crisis and the related burden of disease in developing countries.

ROMA, E. PUGH, I, (2012): Toilets for health. London: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine URL [Visita: 27.11.2012]Water Security Framework

A water security framework which links sustainable WASH services to livelihood, environmental and food security water uses. It sets out fundamental priorities for improving the water security of poor and marginalised people as part of a community based approach to water resource management. The document consists of five parts: (I) Definition and measurement of water security; (II) Threats to community's water security; (III) The four main dimensions of water security; (IV) Community-based water resource management approaches; (V) WaterAid's minimum commitments to ensuring water security.

WATERAID (2012): Water Security Framework. London: WaterAid URL [Visita: 08.08.2012]UN-Water Global Annual Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS). The Challenge of Extending and Sustaining Services

This report is produced every two years by the World Health Organization (WHO) on behalf of UN-Water. It provides a global update on the policy frameworks, institutional arrangements, human resource base, and international and national finance streams in support of sanitation and drinking-water. It is a substantive input into the activities of Sanitation and Water for All (SWA).

WHO (2012): UN-Water Global Annual Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS). The Challenge of Extending and Sustaining Services. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) URL [Visita: 17.04.2013]Interventions to Improve Water Quality and Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Practices, and Their Effects on the Nutritional Status of Children

Water, sanitation and hygiene interventions are frequently implemented to reduce infectious diseases, and may be linked to improved nutrition outcomes in children. The objective of this paper is to evaluate the effect of interventions to improve water quality and supply, provide adequate sanitation and promote handwashing with soap, on the nutritional status of children under the age of 18 years and to identify current research gaps.

DANGOUR, A.D. WATSON, L. CUMMING, O. BOISSON, S. CHE, Y. VELLEMAN, Y. CAVILL, S. ALLEN, E. UAUY, R. (2013): Interventions to Improve Water Quality and Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Practices, and Their Effects on the Nutritional Status of Children. (= Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013 , 8 ). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons URL [Visita: 05.09.2013]How much International Variation in Child Height Can Sanitation Explain?

Physical height is an important economic variable reflecting health and human capital. Puzzlingly, however, differences in average height across developing countries are not well explained by differences in wealth. This paper provides the first documentation of a quantitatively important gradient between child height and sanitation that can statistically explain a large fraction of international height differences.

SPEARS, D. (2013): How much International Variation in Child Height Can Sanitation Explain?. (= Policy Research Working Paper , 6351 ). Washington: The World Bank Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) URL [Visita: 23.09.2013]Sanitation and Hygiene in Africa: Where do we Stand?

This book takes stock of progress made by African countries through the AfricaSan process since 2008 and the progress needed to meet the MDG on sanitation by 2015 and beyond. It addresses priorities which have been identified by African countries as the key elements which need to be addressed in order to accelerate progress.This book is essential reading for government staff from Ministries responsible for sanitation, sector stakeholders working in NGOs, CSOs and agencies with a focus on sanitation and hygiene and water and Sanitation specialists. It is also suitable for Masters courses in water and sanitation and for researchers and the donor community.

CROSS, P. COOMBES, Y. (2013): Sanitation and Hygiene in Africa: Where do we Stand?. Analysis from the AfricaSan Conference, Kigali, Rwanda. London: International Water Association (IWA) Publishing URL [Visita: 01.11.2013]Domestic Water and Sanitation as Water Security

As distinct from many other domains to which the concept of water security is applied, domestic or personal water security requires a perspective that incorporates the reciprocal notions of provision and risk, as the current status of domestic water and sanitation security is dominated by deficiency. This paper reviews the interaction of science and technology with policies, practice and monitoring, and explores how far domestic water can helpfully fit into the proposed concept of water security, how that is best defined, and how far the human right to water affects the situation.

BRADLEY, D.J. ; BARTRAM, J.K. (2013): Domestic Water and Sanitation as Water Security. Monitoring, Concepts and Strategy. Entradas: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: , 371. URL [Visita: 01.11.2013]Hygiene Intervention Reduces Contamination of Weaning Food in Bangladesh

This study was conducted to measure the impact of a hygiene intervention on the contamination of weaning food in Bangladesh.

ISLAM, M.S. ; MAHMUD, Z.H. ; GOPE, P.S. ; ZAMAN, R.U. ; HOSSAIN, Z. ; ISLAM, M.S. ; MONDAL, D. ; SHARKER, M.A.Y. ; ISLAM, K. ; JAHAN, H. ; BHUIYA, A. ; ENDTZ, H.P. ; CRAVIOTO, A. ; CURTIS, V. ; TOUR, O. ; CAIRNCROSS, S. (2013): Hygiene Intervention Reduces Contamination of Weaning Food in Bangladesh. Entradas: Tropical Medicine and International Health: Volume 18 , 250-258. URL [Visita: 25.11.2013]The United Nations World Water Development Report 2015

Water resources, and the range of services they provide, underpin poverty reduction, economic growth and environmental sustainability. From food and energy security to human and environmental health, water contributes to improvements in social wellbeing and inclusive growth, affecting the livelihoods of billions. This report provides a summary on how water and related resources are managed in support of human well-being and ecosystem integrity in a robust economy.

UNESCO UNESCO (2015): The United Nations World Water Development Report 2015. Water for a Sustainable World. Paris: UNESCO URL [Visita: 23.11.2016]Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trials of Individual and Combined Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Nutritional Interventions in Rural Bangladesh and Kenya

Water quality, sanitation, handwashing and nutritional interventions can independently reduce enteric infections and growth faltering. There is little evidence that directly compares the effects of these individual and combined interventions on diarrhoea and growth when delivered to infants and young children. The objective of the WASH Benefits study is to help fill this knowledge gap.

ARNOLD, B.F. ; NULL, C. ; LUBY, S. ; UNICOMB, L. ; STEWART, C. ; DEWEY, K. ; AHMED, T. ; ASHRAF, S. ; CHRISTENSEN, G. ; CLASEN, T. ; DENTZ, H.N. ; FERNALD, L.C.H. ; HAQUE, R. ; HUBBARD, A. ; KARIGER, P. ; LEONTSINI, E. ; LIN, A. ; NJENGA, S.M. ; PICKERING, A.J. ; RAM, P.K. ; TOFAIL, F. ; WINCH, P. ; COLFORD, J.M. (2013): Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trials of Individual and Combined Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Nutritional Interventions in Rural Bangladesh and Kenya. The WASH Benefits Study Design Rationale. Entradas: BMJ Open.: URL [Visita: 09.06.2018] PDFOpen Defecation and Childhood Stunting in India

Poor sanitation remains a major public health concern linked to several important health outcomes; emerging evidence indicates a link to childhood stunting. In India over half of the population defecates in the open; the prevalence of stunting remains very high. Recently published data on levels of stunting in 112 districts of India provide an opportunity to explore the relationship between levels of open defecation and stunting within this population.

SPEARS, D. ; GHOSH, A. ; CUMMING, O. (2013): Open Defecation and Childhood Stunting in India. An Ecological Analysis of New Data from 112 Districts. Entradas: PLOS ONE: Volume 9 URL [Visita: 10.06.2018] PDFVillage Sanitation and Children's Human Capital

Open defecation is exceptionally widespread in India, a country with puzzlingly high rates of child stunting. This paper reports a randomized controlled trial of a village-level sanitation program implemented in one district by the government of Maharashtra. The program caused a large but plausible average increase in child height, which is an important marker of human capital. The results demonstrate sanitation externalities: an effect even on children in households that did not adopt latrines.

HAMMER, J. SPEARS, D. (2013): Village Sanitation and Children's Human Capital. Evidence from a Randomized Experiment by the Maharashtra Government. (= Policy Research Working Paper , 6580 ). Washington: The World Bank Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) URL [Visita: 01.10.2013]SDG 6 along the water and nutrient cycles

This AGUASAN publication illustrates how the water and nutrient cycles can be used as a tool for creating a common understanding of a water and sanitation system and aligning it with SDG 6.

BROGAN, J., ERLMANN, T., MUELLER, K. and SOROKOVSKYI, V. (2017): SDG 6 along the water and nutrient cycles. Using the water and nutrient cycles as a tool for creating a common understanding of a water and sanitation system - including workshop material. Bern (Switzerland): AGUASAN and Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) URL [Visita: 26.03.2019] PDFDirty Little Secret: The Loo that Saves Lives in Liberia

Diarrhoea kills more children than HIV/Aids, tuberculosis and malaria combined – and its main cause is food and water contaminated with human waste. Liberia's president is trying to change all that.

GEORGE, R. (2012): Dirty Little Secret: The Loo that Saves Lives in Liberia. London: The Guardian URL [Visita: 13.02.2012]