Menstruation is a natural process. However, in most parts of the world, it remains a taboo and is rarely talked about (HOUSE et al. 2012).

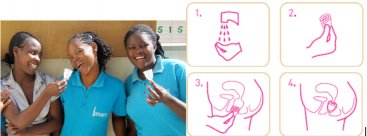

Young women chatting about menstrual issues. Source: UNICEF (2008)

Many cultures have beliefs, myths and taboos relating to menstruation. Almost always, there are social norms or unwritten rules and practices about managing menstruation and interacting with menstruating women. Some of these are helpful but others have potentially harmful implications. For example, in some cultures, women and girls are told that during their menstrual cycle they should not bathe (or they will become infertile), touch a cow (or it will become infertile), look in a mirror (or it will lose its brightness), or touch a plant (or it will die) (HOUSE et al. 2012).

Cultural norms and religious taboos on menstruation are often compounded by traditional associations with evil spirits, shame and embarrassment surrounding sexual reproduction. For example, in Tanzania, some believe that if a menstrual cloth is seen by others, the owner of the cloth may be cursed (HOUSE et al. 2012).

Most striking is the restricted control which many women and girls have over their mobility and behaviour due to their ‘impurity’ during menstruation, including the myths, misconceptions, superstitions and (cultural and/or religious) taboos concerning menstrual blood and menstrual hygiene (TEN 2007). The figure below details examples of these restrictions in several Asian countries. Similar restrictions are practised in other countries around the world.

Restrictions on girls during their menstru al period in Afghanistan, India, Iran and Nepal. Source: HOUSE et al. (2012)

Having said this, it is important to recognise the potential for intra-cultural variations in the interpretation of meanings of menstruation, and how ‘taboos’ may in fact serve the interests of women, even if at first glance they appear to be negative. For example, women may appreciate the ‘banishment’ to menstrual huts as they are given a rest period from the normal intensity of daily chores (KIRK & SOMMER 2006).

Remarkable is also that the education by parents concerning reproductive health, sexuality and all related issues is considered almost everywhere as a “no-go” area (TEN 2007). It appears that in much of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, girls’ level of knowledge and understanding of puberty, menstruation and reproductive health are very low (KIRK & SOMMER 2006).

The taboo of menstruation helps to inflict indignity upon millions of women and girls, but it also does worse: The grave lack of facilities and appropriate sanitary products can push menstruating girls out of school, temporarily and sometimes permanently (see also water sanitation and gender).

Stigma around menstruation and menstrual hygiene is a violation of several human rights, most importantly of the right to human dignity, but also the right to non-discrimination, equality, bodily integrity, health, privacy and the right to freedom from inhumane and degrading treatment from abuse and violence (WSSCC 2013).

Actually, there is a relation between menstrual hygiene and school drop-out of girls from the higher forms (grade four and five) of primary and secondary education (see also water sanitation and gender). Research confirms that the onset of puberty leads to significant changes in school participation among girls. In spite of the fact that Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 2 (achieve universal primary education) has been accomplished in the lower forms of primary education in many developing countries, the participation of girls, in particular in Africa and Asia, lags far behind the participation of boys in the higher forms of primary and secondary education. Besides the fact that girls are married off at an early age in some cultures, many girls are kept at home when they start menstruating, either permanently (drop-out) or temporarily during the days they menstruate. When girls get left behind this can eventually also lead to school drop-out (TEN 2007).

The monthly menstruation period also creates obstacles for female teachers. They either report themselves sick or go home after lessons as fast as possible and do not have enough time to give extra attention to children who need it. The gender–unfriendly school culture and infrastructure and the lack of adequate menstrual protection alternatives and/or clean, safe and private sanitation facilities for female teachers and girls undermine the right of privacy, resultingin a fundamental infringement of the human rights of female teachers and girls. Consequently, girls and women get left behind and there is no equal opportunity. Due to this obstacle, MDG 3 (promote gender equality and empower women) cannot be achieved either (TEN 2007).

Adapted from HOUSE et al. (2012) and KIRK & SOMMER (2006)

There are also health issues to consider apart from the above-mentioned social issues. Poor protection and inadequate washing facilities may increase susceptibility to infection, with the odour of menstrual blood putting girls at risk of being stigmatised (see also water sanitation and health. In communities where female genital cutting is practiced, multiple health risks exist. Where the vaginal aperture is inadequate for menstrual flow, a blockage and build-up of blood clots is created behind the infibulated area. This can be a cause for protracted and painful period, increased odour, discomfort and the potential for additional infections (KIRK & SOMMER 2006).

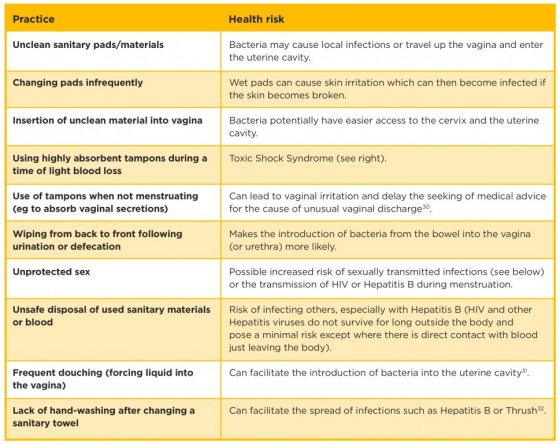

It is assumed that the risk of infection (including sexually transmitted infection) is higher than normal during menstruation because the blood coming out of the body creates a pathway for bacteria to travel back into the uterus. Certain practices are more likely to increase the risk of infection (see figure below). Using unclean rags for example, especially if they are inserted into the vagina, can introduce or support the growth of unwanted bacteria that could lead to infection.

As an example, findings from Bangladesh, where 80% of factory workers are women, show that 60% of them were using rags from the factory floor for menstrual cloths. These are highly chemically charged and often freshly dyed. Infections are common, leading to 73% of women missing work for on average six days a month. Women had no safe place either to purchase cloth or pads or to change/dispose of them. When women are paid by piece, those six days away present a huge economic damage to them but also to the business supply chain (WSSCC 2013).

Potential risks to health of poor menstrual hygiene. Source: HOUSE et al. (2012)

Infrequently mentioned in studies conducted in developing countries are the simple discomforts, such as lower back pain, bloating, cramping, mood swings, and other symptoms related to menstruation that have been well documented in Western literature. Whereas girls in developed countries generally have access to a range of general – and specific – painkillers and other pharmacological products, girls experiencing similar symptoms in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia do not have access to such ‘luxuries’.

Sanitary Protection Materials and Disposal

The choice of sanitary protection is very much a personal decision based on cultural acceptability. It is often influenced by a woman’s or girl’s environment and access to funds, water supply and affordable options. It is critical that any programme aiming to support women or girls with sanitary protection materials involves them in the planning discussions and decisions about the options to be supported (see also deciding with the community and planning with the community).

Menstrual cups and how to use them. Source: RUBY CUP (2013)

Disposable sanitary towels are the most frequently used methods of managing menstruation. In resource-poor settings they are often prohibitively expensive, bulky to transport and difficult to dispose of. Many women and adolescent girls from poor families cannot afford to buy these hygienic towels (APHRC 2010). Some girls may even be led to trade sex for small amounts of money in order to purchase sanitary protection materials (KIRK & SOMMER 2006). But sanitary pads reduce the barriers for girls to stay in school, which are multiple: fear of soiling, fear of odour, and even if there are WASH facilities at school, fear of leaving visible blood in the latrine or toilet (WSSCC 2013).

Cloths or cloth pads may be a sustainable sanitary option, but it must be hygienically washed and dried in the sunlight. Sunlight is a natural steriliser and drying the cloth pads on sunlight sterilises them for future use. They also need to be stored in a clean dry place for reuse. Girls who do not know what menstruation is can have little hope of managing it safely or hygienically, as a workshop participant demonstrated when she shared her own experience of growing up in Sierra Leone: “Me and my sisters all hid our sanitary cloths under the bed to dry, out of shame.” Her experience is common worldwide: many participants shared anecdotes from field studies and interviews of girls and women who attempt to dry their cloths out of sight. In practice, this means hiding them in a damp and unhygienic place (UNICEF 2008; WSSCC 2013).

The menstrual cup may be an appropriate new technology for poor women and girls. It is a cup made of medical silicone rubber that is inserted into the vagina to collect menstrual blood. It needs to be removed and emptied less frequently than sanitary pads. That reduces the problems young women face in lacking privacy and facilities to change and dispose of sanitary products in schools and other contexts. This technology may offer a sustainable, practical and cost-effective alternative. It is recommended that when using the menstrual cup one needs to maintain a high standard of hygiene especially during insertion, removal and general cleaning. Although water shortages could present challenges for its use, the amount of water required when using the menstrual cup is minimal compared to other methods (APHRC 2010). Offering menstrual cups can be a social business opportunity for the private sector, as shown by experiences from Kenya (RUBY CUP 2013).

The table below compares the advantages and disadvantages of further sanitary materials (HOUSE et al. 2012).

| Sanitary protection option | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Natural materials (e.g. mud, cow dung, leaves) |

|

|

| Strips of clothes |

|

|

| Toilet paper or tissues |

|

|

| Re-usable pads |

|

|

| Tampons |

|

|

| Menstrual cups |

|

|

| Panties/Underwear |

|

|

Advantages and disadvantages of different sanitary protection materials. Adapted from HOUSE et al. (2012)

Sanitary Infrastructure

Adapted from KIRK & SOMMER (2006)

From a very practical perspective, girls who lack adequate sanitary materials may miss school each month during their period (see also water sanitation and gender). If girls attend schools which lack adequate latrines and water supplies to comfortably change sanitary materials and wash themselves in privacy, they may be unable to remain comfortably in class during their menstrual cycle (see also sater sanitation and dignity. The absence of clean and private sanitation facilities that allow for menstrual hygiene may discourage girls from attending school when they menstruate. UNICEF (2005) estimates that about 1 in 10 school-age African girls do not attend school during menstruation or drop out at puberty because of the lack of clean and private sanitation facilities in schools.

Poor sanitary facilities in schools also affect women teachers’ experiences. Given the unavailability of substitute teachers due to teacher shortages all over the developing world, this leads to reduced teachers’ instruction time by 10-20% (WORLD BANK 2005).

Where girls are able or determined to attend school throughout menstruation, insufficient facilities and sanitary protection may nevertheless create discomfort in the classroom and an inability to participate. For example, menstruating girls may hesitate to go up to the front of the class to write on the board, or to stand up as is often required for answering teachers’ questions, due to fear of having an ‘accident’ and staining their uniforms.

To manage menstruation hygienically, it is essential that women and girls have access to water and sanitation (see also access to water and sanitation. They need a safe, private space to change sanitary materials; clean water for washing their hands and used cloths; and facilities for safely disposing used materials or a place to dry them if reusable.

Disposal

Last but not least, good management of menstrual hygiene should obviously include safe and sanitary disposal. This is widely lacking. Where do girls and women dispose of their sanitary products and cloths? Wherever they can do so secretly and easily. In practice, this means the nearest open defecation field, river or garbage dump. This applies to both commercial and home-made sanitary materials (WSSCC 2013). In developing countries, which frequently have poor waste management infrastructure, this type of waste will certainly produce larger problems (see also health risk management). For this reason, encouraging menstrual hygiene in developing countries must be accompanied with calculated waste management strategies (TEN 2007).

Neglecting menstrual hygiene in WASH programmes could also have a negative effect on sustainability. Failing to provide disposal facilities for used sanitary materials can result in blocked latrines becoming blocked and quickly filling pits (HOUSE et al. 2012).

Yet, adequate facilities and sanitary protection materials are only part of the solution. In addition, it is necessary to go beyond the practical issues of menstrual management in schools and workplaces, and to use the vehicle of education. Education and information (in combination with hygiene and sex education) empowers women and girls with factual information about their bodies and how to look after them (KIRK & SOMMER 2006) (for example through invalid link or part of invalid link). Presently, teachers are rarely trained in teaching menstrual hygiene and consequently rarely teach it. Male teachers may feel cultural norms forbid them from discussing such topics with young girls. As a result, MHM is either taught late or not at all (WSSCC 2013).

Empowering women and girls is also necessary so that their voices are heard and their menstrual hygiene needs are taken into account (see also awareness raising). Because a lack of factual information compounded by the prevalence of myths means that girls’ practical needs related to managing menstruation are often not appreciated or appropriately addressed (KIRK & SOMMER 2006) (see also invalid link).

Community wide approaches (see also planning with the community), which specifically involve boys and men, are promising ways of improving MHM. Physical barriers to girls and women because of inadequate sanitary means are often connected to social barriers like taboos and stigmas and need to be considered together.

Another software tool to improve women’s dignity are days off work whilst having their monthly periods. In Zambia, for example, every working woman is entitled by law to one day off work each month to ensure that women function at their best. This day is referred to as „Mother’s day“. Although there are no specifics, it is a silent belief that it was set up to accord a woman a day’s relief whilst having her monthly periods (MYWAGE 2013). A day off work must not mean less economic performance for a business as women may regenerate more energy to outweigh the day off.

Attitudes Towards, and Acceptability of, Menstrual Cups as a Method for Managing Menstruation: Experiences of Women and Schoolgirls in Nairobi, Kenya

The issue 21 of the APCHR policy brief highlights key findings from a feasibility study on the menstrual cup as a method for managing menstrual flow among adolescent girls and women in Nairobi, Kenya. The findings provide insights into their attitudes towards the menstrual cup prior to use, their acceptability, and experiences of using the menstrual cup. It aims at providing evidence for better understanding of the menstrual cup as a method for managing menstrual flow, and whether it is an appropriate and acceptable method among adolescent girls and women in Kenya.

APHRC (2010): Attitudes Towards, and Acceptability of, Menstrual Cups as a Method for Managing Menstruation: Experiences of Women and Schoolgirls in Nairobi, Kenya. Nairobi: The African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Use of Menstrual Cup by Adolescent Girls and Women. Potential Benefits and Key Challenges

This policy brief is based on field research and a feasibility study. It shows that there are tremendous benefits, which will ultimately contribute to the promotion of the reproductive health and education rights of adolescent girls and women.

APHRC (2010): Use of Menstrual Cup by Adolescent Girls and Women. Potential Benefits and Key Challenges. Nairobi: The African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Menstrual hygiene matters

Menstrual hygiene matters is an essential resource for improving menstrual hygiene for women and girls in lower and middle-income countries. Nine modules and toolkits cover key aspects of menstrual hygiene in different settings, including communities, schools and emergencies.

HOUSE, S. MAHON, T. CAVILL, S. (2012): Menstrual hygiene matters. A resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world. London: WaterAid URL [Visita: 29.01.2013]Menstruation and Body Awareness. Linking Girls Health With Girls Education

This paper examines the relationships between adolescent girls’ health and well-being with a particular emphasis on the intersection between post-pubescent girls’ menstrual management and education. The paper focuses on developing country contexts, such as sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, where physical, socio-cultural, and economic challenges may render girls’ menstrual management in school particularly difficult.

KIRK, J. SOMMER, M. (2006): Menstruation and Body Awareness. Linking Girls Health With Girls Education. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) URL [Visita: 30.07.2013]Take a “Moher’s Day” – It’s Your Right!

Menstrual Hygiene. A Neglectted Condition for the Achievement of Several Millennium Development Goals

Until now, poor menstrual hygiene in developing countries has been an insufficiently acknowledged problem. This paper draws attention to the relationship between menstrual hygiene and school drop–out rates for girls from the higher forms of primary (grade 4 & 5) and secondary education. Several Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) will not be achieved if several state and non–state actors do not undertake immediate action.

TEN, V.T.A. (2007): Menstrual Hygiene. A Neglectted Condition for the Achievement of Several Millennium Development Goals. Zoetermeer: Europe External Policy Advisors (EEPA) URL [Visita: 11.08.2013]Sharing simple facts. Useful Information about Menstrual Health and Hygiene

This is a self-reference guidance booklet for adolescent girls and young women. It provides simple factual information about the process of menstruation, its management in a safe and hygienic manner and the myths and taboos associated with it.

UNICEF (2008): Sharing simple facts. Useful Information about Menstrual Health and Hygiene. New York: United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) URL [Visita: 08.03.2013]Sanitation

This website provides information of the monitoring on the sanitation situation for children and women.

UNICEF (2005): Sanitation. URL [Visita: 30.07.2013]Menstruation Hygiene Management for Schoolgirls in Low-Income Countries

This factsheet outlines the problems experienced by menstruating schoolgirls in low-income countries. Although its focus is predominantly sub-Saharan Africa, many of the issues raised are relevant to girls in most low-income countries, although there may be differences in popular practices and beliefs. The factsheet also evaluates simple solutions to these problems including the use of low-cost sanitary pads, and suggests ways in which Menstruation Hygiene Management (MHM) can be included in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programmes. It considers how menstrual practices are affected by cultural beliefs and the lack of education both at home and at school.

CROFTS, T. (2012): Menstruation Hygiene Management for Schoolgirls in Low-Income Countries. (= Fact Sheet 7 ). Loughborough: Water, Engineering and Development Center (WEDC) URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Toolkit on Hygiene, Sanitation and Water in Schools

Hygiene, Sanitation, and Water in Schools projects can create an enabling learning environment that contributes children's improved health, welfare, and learning performance. This Toolkit makes available information, resources, and tools that provide support to the preparation and implementation of hygiene, sanitation, and water in schools policies and projects.

WORLD BANK ; UNICEF ; WSP (2001): Toolkit on Hygiene, Sanitation and Water in Schools. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank URL [Visita: 22.04.2019]Celebrating Womanhood: How Better Menstrual Hygiene Management is the Path to Better Health, Dignity and Business

Final report from the International Women’s Day event arranged in Geneva in March 2013 by WSSCC.

WSSCC (2013): Celebrating Womanhood: How Better Menstrual Hygiene Management is the Path to Better Health, Dignity and Business. London: Water Supply & Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) URL [Visita: 11.09.2013]Menstruation Hygiene Management for Schoolgirls in Low-Income Countries

This factsheet outlines the problems experienced by menstruating schoolgirls in low-income countries. Although its focus is predominantly sub-Saharan Africa, many of the issues raised are relevant to girls in most low-income countries, although there may be differences in popular practices and beliefs. The factsheet also evaluates simple solutions to these problems including the use of low-cost sanitary pads, and suggests ways in which Menstruation Hygiene Management (MHM) can be included in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programmes. It considers how menstrual practices are affected by cultural beliefs and the lack of education both at home and at school.

CROFTS, T. (2012): Menstruation Hygiene Management for Schoolgirls in Low-Income Countries. (= Fact Sheet 7 ). Loughborough: Water, Engineering and Development Center (WEDC) URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Low Cost Handmade Sanitary Pads! From Design to Production. A Step Forward in Menstrual Hygiene Promotion in Pakistan

In order to manage the basic phenomena of menstruation, sanitary materials are used by women of all ages, almost all from 14 to 45 years of age. Though branded material is available in urban areas while difficult to access in rural, in those areas where such materials are available, they are expensive and difficult to afford and manage as well. It has been planned by IRSP to introduce Menstruation Hygiene Management (MHM) specific low cost technologies in Pakistan for not just providing ease in their practices but also for paving way for women empowerment through involving them in large-scale sanitary pad production.

ISRAR, H. NASIR, S. (2012): Low Cost Handmade Sanitary Pads! From Design to Production. A Step Forward in Menstrual Hygiene Promotion in Pakistan. Shiekh Maltoon Town: Integrated Regional Support Program (IRSP) URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Menstrual Hygiene Management in Africa

This presentation addressed the issue of menstruation hygiene management, which in the past has not received the need attention in the circles of sanitation and hygiene. The presenter touched on myths and cultural taboos mainly from Africa surrounding menstruation, adaption methods of menstruation, high cost of sanitary materials, and inadequate sanitation facilities as well as their ill-effects on education and development of the girl-child.

MOMA, L. (n.y): Menstrual Hygiene Management in Africa. (= Presentation at 4th African Water Week ). London: WaterAid URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Review of Sanitation System Interactions with Menstrual Hygiene Practices

This presentation describes a research project undertaken by the Stockholm Environmental Institute (SEI). It addresses the interactions between menstrual management and sanitation, using a systems approach that integrates an understanding of the sanitation hardware with women’s practices, needs and willingness to pay for menstrual management products. Study sites are Durban, South Africa and Bihar, India.

KJELLEN, M. PENSULO, C. (2012): Review of Sanitation System Interactions with Menstrual Hygiene Practices. (= Presentation to the 16th SuSanA Meeting ). Stockholm: Stockholm Environmental Institute (SEI) URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Global Review of Sanitation System Trends and Interactions with Menstrual Management Practices

The problem with disposing of menstrual waste into pit latrines is that it causes the pits to fill up faster. The excreta in the pit decompose and decrease in volume, while the non-biodegradable components of menstrual waste accumulate and do not break down. Furthermore, once the sludge has been removed from the pit latrine, if it is to be used in agriculture, any waste that has not completely decomposed such as menstrual pads must be removed before the sludge can be composted or applied to farmland. The cost to remove, screen, and dispose of menstrual management products from pit latrine sludge is high and not accounted for.

KJELLEN, M. PENSULO, C. NORDQVIST, P. FODGE, M. (2012): Global Review of Sanitation System Trends and Interactions with Menstrual Management Practices. Report for the Menstrual Management and Sanitation Systems Project . Stockholm: Stockholm Environment Institute URL [Visita: 15.01.2013]Getting it Right. Improving Maternal Health Through Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

‘Getting it Right’ is a literature review addressing the impact of water, sanitation and hygiene on maternal mortality. It includes the specific linkages that were found as well as recommendations from the authors.

SHORDT, K. SMET, E. (2012): Getting it Right. Improving Maternal Health Through Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. Haarlem: Supporting Healthy Solutions by Local Communities (SIMAVI) URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Menstrual Hygiene Management in Humanitarian Emergencies. Gaps and Recommendations

This article is an effort to begin to document the recommendation of key multi-disciplinary experts working in humanitarian response on effective approaches to Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) in emergency contexts, along with a summarising the existing literature, and the identification of remaining gaps in MHM practice, research and policy in humanitarian contexts.

SOMMER, M. (2012): Menstrual Hygiene Management in Humanitarian Emergencies. Gaps and Recommendations. Entradas: Waterlines: Volume 31 , 83-104. URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Utilizing Participatory and Quantitative Methods for Effective Menstrual-Hygiene Management Related Policy and Planning

Capturing girls’ voiced experiences of the transition through puberty and menstrual onset through the use of participatory methods is critical and long overdue. Coupled with demographic and quantitative data it enables generalisation of findings to national education and adolescent health policy. The subject of this paper is to offer a review of the evidence to date on menstrual-hygiene management research, programming and policy, as well as on remaining gaps in menstrual-related research and recommended methodological approaches.

SOMMER, M. (2010): Utilizing Participatory and Quantitative Methods for Effective Menstrual-Hygiene Management Related Policy and Planning. (= Paper for the UNICEF-GPIA Conference 2010 ). New York: Mailman School for Public Health URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Sanitation Matters - A Magazine for Southern Africa

Content in this issue: A Tool For Measuring The Effectiveness Of Handwashing p. 3-7; Five Best Practices Of Hygiene Promotion Interventions In the WASH Sector p. 8-9; Washing Your Hands With Soap: Why Is It Important? p. 10-11; Appropriate Sanitation Infrastructure At Schools Improves Access To Education p. 12-13; Management Of Menstruation For Girls Of School Going Age: Lessons Learnt From Pilot Work In Kwekwe p. 14 -15; WIN-SA Breaks The Silence On Menstrual Hygiene Management p. 16; Joining Hands To Help Keep Girls In Schools p. 17; The Girl-Child And Menstrual Management :The Stories Of Young Zimbabwean Girls. p. 18-19; Toilet Rehabilitation At Nciphizeni JSS And Mtyu JSS Schools p. 20 - 23; Celebratiing 100% sanitation p. 24 - 26.

WATER INFORMATION NETWORK (2012): Sanitation Matters - A Magazine for Southern Africa. South Africa: Water Information Network URL [Visita: 19.06.2019]We Can't Wait

This report is on the impact of poor sanitation on the safety, well-being, and educational prospects of women. Girls’ lack of access to a clean, safe toilet, especially during menstruation, perpetuates risk, shame, and fear. This has long-term impacts on women’s health, education, livelihoods, and safety but it also impacts the economy, as failing to provide for the sanitation needs of women ultimately risks excluding half of the potential workforce.

WATERAID ; UNILEVER DOMESTOS ; WSSCC (2013): We Can't Wait. A Report on Sanitation and Hygiene for Women and Girls. London / Geneva: WaterAid, Unilever Domestos, Water Supply & Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) URL [Visita: 11.01.2014]A Community Based Study on Menstrual Hygiene Among Adolescent Girls

The research was undertaken to explore knowledge, the status of hygiene, and practices regarding menstruation among adolescent girls in an urban slum areas. A total of 360 adolescent girls participated in the study around the urban health training centre at Guntur

JOGDAND, K. ; YERPUDE, P. (2011): A Community Based Study on Menstrual Hygiene Among Adolescent Girls. Entradas: Indian Journal of Maternal and Child Health: Volume 13 , 1-6. URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]School Menstrual Hygiene Management in Malawi: More than Toilets

This study identifies the needs and experiences of girls regarding menstruation. It draws upon participatory group workshops, a questionnaire and semi structured interviews with school-age girls in Malawi to make various recommendations, including lessons about menstrual hygiene management (MHM), girl-friendly toilet designs, and the provision of suitable and cheap sanitary protection.

PIPER-PILLITTERI, S. (2012): School Menstrual Hygiene Management in Malawi: More than Toilets. London: WaterAid URL [Visita: 17.03.2012]Is Menstrual Hygiene and Management an Issue for Adolescent School Girls? A Comparative Study of Four Schools in Different Settings of Nepal

The study shows that adolescent girls face restrictions during menstruation due to widely held beliefs and due to physical conditions. This affects both how often and how well they attend school. There is an urgent need to address entrenched and incorrect menstrual perceptions and enable proper hygiene management in schools.

WATERAID (2009): Is Menstrual Hygiene and Management an Issue for Adolescent School Girls? A Comparative Study of Four Schools in Different Settings of Nepal. London: WaterAid URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Assessment of Beliefs and Practices Relating to Menstrual Hygiene of Adolescent Girls in Lebanon

Poor menstrual hygiene prevents achieving several Millennium Development Goals. The aim of this study was to assess menstrual hygiene practices based on sociocultural beliefs of adolescent girls in Lebanon.

SANTINA, T. ; WEHBE, N. ; ZIADE, F.M. ; NEHME, M. (2013): Assessment of Beliefs and Practices Relating to Menstrual Hygiene of Adolescent Girls in Lebanon. Entradas: International Journal of Health Sciences and Research: Volume 3 , 75-88. URL [Visita: 03.02.2014]A Guide to Personal Hygiene

This poster is part of the series of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene posters designed by the Water, Engineering and Development Center of Loughborough University.

INCE, M.E. SHAW, R. DAVEY, K. (2013): A Guide to Personal Hygiene. Poster. (= WEDC Posters , 3 ). London: Water, Engineering and Development Center (WEDC) URL [Visita: 28.08.2013]Menstrual hygiene matters

Menstrual hygiene matters is an essential resource for improving menstrual hygiene for women and girls in lower and middle-income countries. Nine modules and toolkits cover key aspects of menstrual hygiene in different settings, including communities, schools and emergencies.

HOUSE, S. MAHON, T. CAVILL, S. (2012): Menstrual hygiene matters. A resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world. London: WaterAid URL [Visita: 29.01.2013]Growing Up at School. A Guide to Menstrual Management for School Girls

This booklet has been developed to help school girls manage the critical period when they enter adolescence and commence menstruation between the ages of 10 and 14. The booklet describes the changes that take place in young girls during this period and provides tips on personal hygiene, sanitary pads usage, and pain management.

KANYEMBA, A. (2011): Growing Up at School. A Guide to Menstrual Management for School Girls. Pretoria: Water Research Commission (WRC) URL [Visita: 08.03.2013]Addressing Water and Sanitation Needs of Displaced Women in Emergencies

Mainstreaming gender in an emergency Water and Sanitation response can be difficult as standard consultation and participation processes take too much time in an emergency. To facilitate a quick response that includes women's needs, a simple Gender and WatSan Tool has been developed that can also be used by less experienced staff.

LANGE, R. de (2013): Addressing Water and Sanitation Needs of Displaced Women in Emergencies. (= WEDC International Conference, Nakuru, Kenya , 36 ). Leicestershire: Water, Engineering and Development Centre (WEDC) URL [Visita: 11.01.2014]Making Connections. Women Sanitation and Health Event 29 April 2013

On 29th April, SHARE Research Consortium hosted the event 'Making connections: Women, sanitation and health'. It brought together a diverse mix of speakers from the WASH, gender and health sectors to debate issues such as violence against women, menstrual hygiene management and maternal health.

SHARE (2013): Making Connections. Women Sanitation and Health Event 29 April 2013. (= Proceedings of the Women Sanitation and Health Event, 19th of April 2013). London: Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) URL [Visita: 15.05.2013]Growth and Changes

This book provides simple and illustrated explanations about the changes faced by girls during puberty, i.e. physical changes, menstruation, menstrual hygiene and pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS). The book is adapted to local reality and translated into Twi, one of the local languages. It also includes a series of real-life stories told by the girls of Ghana and a section with ‘true or false’, ‘how to’, and ‘is it normal if’ answered questions.

ACKATIA-ARMAH, T.N. SOMMER, M. (2012): Growth and Changes. Accra: Smartline Publishers URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Menstrual Cup. Frequently Asked Questions

Information pamphlet on the use of the menstrual cup. Available in English and Swahili.

APHRC (2010): Menstrual Cup. Frequently Asked Questions. Upper Hill: African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) URL [Visita: 06.08.2013]Growth and Changes. Menstrual Hygiene Education Cambodia

The Cambodian edition of Growth and Changes, in both Khmer and English provides simple and illustrated explanations adapted to local reality about the changes faced by girls during puberty, i.e. physical changes, menstruation, menstrual hygiene, pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS). It also includes a series of real-life stories told by the girls of Cambodia and a section with ‘true or false’, ‘how to’, and ‘is it normal if’ answered questions.

SOMMER, M. CONOLLY, S. (2012): Growth and Changes. Menstrual Hygiene Education Cambodia. Cambodia: Grow and Know Inc. URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Growth and Changes. Menstrual Hygiene Education Tanzania

This booklet tells the stories of young Tanzanian girls, and is a small guide for education on puberty, menstrual hygiene and health. It is bilingual in English and Kishuali. It is also available in Khmer (Cambodia) and in Twi (one of the local languages in Ghana).

SOMMER, M. (2009): Growth and Changes. Menstrual Hygiene Education Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Grow and Know Inc. URL [Visita: 05.08.2013]Sharing simple facts. Useful Information about Menstrual Health and Hygiene

This is a self-reference guidance booklet for adolescent girls and young women. It provides simple factual information about the process of menstruation, its management in a safe and hygienic manner and the myths and taboos associated with it.

UNICEF (2008): Sharing simple facts. Useful Information about Menstrual Health and Hygiene. New York: United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) URL [Visita: 08.03.2013]http://www.shareresearch.org/making_connections

Videos of the Presentations at the Women, Sanitation and Health Event on 29th April 2013. It brought together a diverse mix of speakers from the WASH, gender and health sectors to debate issues such as violence against women, menstrual hygiene management and maternal health.

http://www.susana.org/

In this presentation video, the issue of menstruation hygiene management, which in the past has not received the need attention in the circles of sanitation and hygiene, is being addressed. The presenter touches on myths and cultural taboos mainly from Africa surrounding menstruation, adaption methods of menstruation, high cost of sanitary materials, and inadequate sanitation facilities as well as their ill-effects on education and development of girls.

http://www.aphrc.org/

According to statistics, thousands of girls miss school during their menstrual cycle due to lack of access to sanitary products. The situation remains dire despite a government attempt to subsidise the price of sanitary towels. Now, a research institution has come up with an alternative solution to this problem with an innovation known as 'the moon cup'. Kathryn Omwandho explains.