Spate irrigation is a crop irrigation technique consisting of diverting seasonal stormwater from valleys, rivers, riverbeds and gullies by gravity onto farmland situated at a lower elevation than the flood water. The flood water is then diverted to the fields. This may be done by free intakes, by diversion spurs or by bunds. On the field, there are basically four methods of water distribution. Field-to-field distribution, individual field distribution and extensive or intensive distribution. After the land is inundated crops are sown, sometimes immediately, but often the moisture is stored in the soil profile and used later. Spate irrigation is unique to arid and semi-arid regions bordering highlands. It is important that water rights and requirements of down-stream farmers are considered to avoid conflicts.

| In | Out |

|---|---|

Food Products |

Spate irrigation is a water management system that is unique to semi-arid regions. It is found in the Middle East, North Africa, West Asia, East Africa and parts of Latin America. Surface runoff from mountain catchments is distributed to riverbeds (so-called wadis, the Arabic term for valley, referring to a dry riverbed that contains water only during times of heavy rain) and spread over large areas. Some of the floodwater in sandy riverbeds sinks into the voids between the sand particles where it replaces air, which escapes to the surface of the flood water in thousands of bobbles making the floodwater look as if it was boiling.

Spate irrigation systems contain a big risk and uncertainty. The uncertainty comes both from the unpredictable nature of the floods and the frequent changes of the riverbeds from which the water is diverted. Moreover, it is important that water rights and requirements of down-stream farmers are considered to avoid conflicts. Spate irrigation is often used by the poorest segments of the rural population. They have developed substantial local wisdom in organising spate systems and managing both the flood water and the heavy sediment loads that go along with it (SPATE IRRIGATION NETWORK n.y.). However, spate irrigation is a largely neglected and forgotten form of resource management, in spite of its potential to contribute to poverty alleviation, adaptation to climate change and local food security.

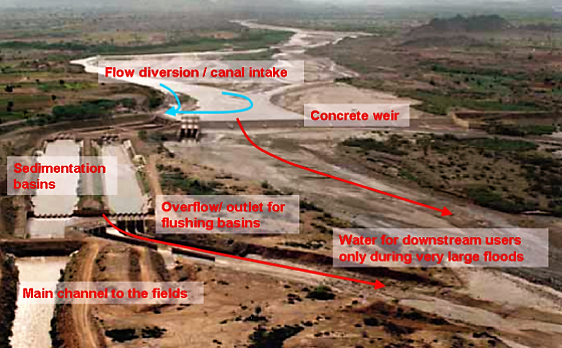

Wadi hydrology is characterised by a great variation in the size and frequency of floods, which directly influence the availability of stormwater for irrigation and agriculture. Wadis have very high sediment loads (therefore sedimentation beds are necessary) and important groundwater recharge through seepage in the wadi bed. For the design of spate irrigation a good estimate of these main hydrological characteristics is required (FAO 2010). This estimate can be done based on technical measurements and estimation, but also the knowledge of the local farmers should be considered.

Generally, a spate irrigation system consists of intake areas or canals within the wadi where the stormwater flow is diverted, sedimentation basins, the channels bringing the water to the field, and overflow to flush the sedimentation basins. When designing the intake, it is important that water requirements of down-stream farmers are considered.

On the Field

(adapted from FAO 2010)

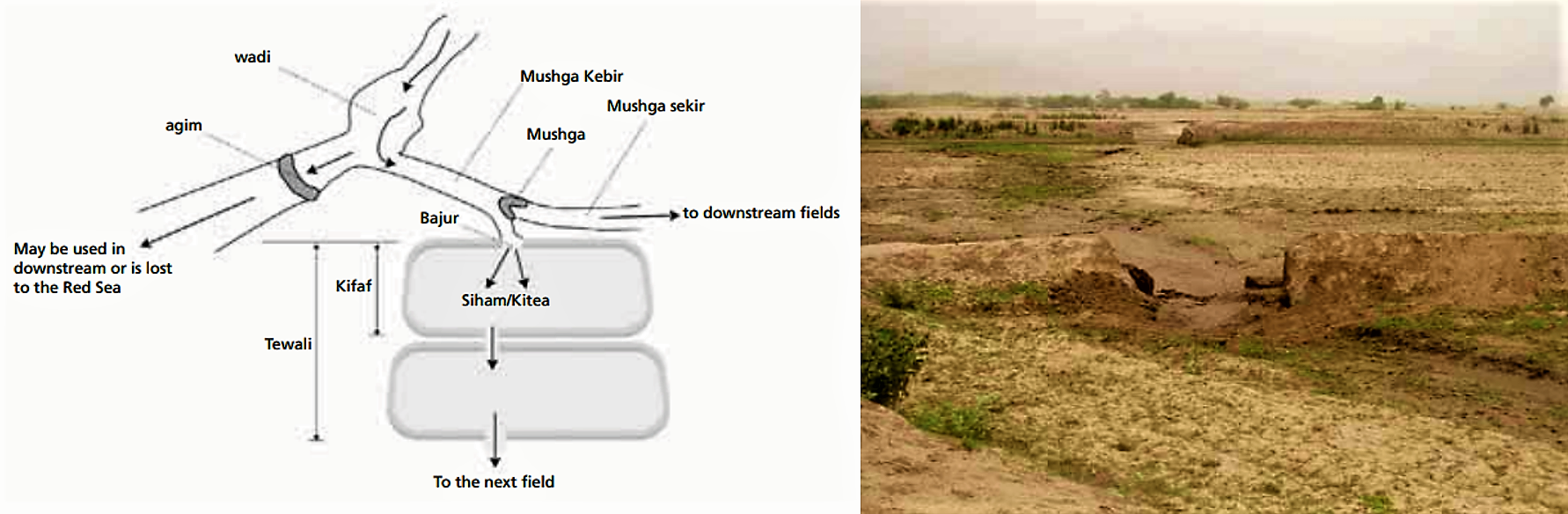

After the water is diverted from the wadis it has to be distributed on the fields. Even though the water flows over the field surface, it is a big difference in contrast to the common surface irrigation methods. Basically, there are four methods, which are commonly known for distributing water at field level in spate irrigation. These methods are grouped into two practices: (1) field-to-field distribution or individual field distribution; and (2) extensive distribution or intensive distribution.

In field-to-field irrigation, all the flow in a canal is diverted to a group of bunded fields by an earthen bund that blocks the canal. When the upstream field of the group commanded by the canal bund is irrigated, water is released by making a cut in the downstream field bund to release water to the next field. This process is repeated until all the fields in commode have been irrigated. The alternative to field-to-field distribution is to supply fields from individual inlets on secondary or tertiary canals. They offer a higher control of water distribution. They help to reduce scours and allow irrigating downstream fields without damaging upstream fields. On the other hand they need more land area for the secondary or tertiary canal construction.

Another difference in the method of water distribution at field level is whether irrigation is spread widely or concentrated in a small area. Whereas in extensive systems a single irrigation is common over the whole surface (extensive distribution), fields may be irrigated twice or three times before cultivation when floods are concentrated on a small area (intensive distribution). Both types can exist in the same system and are dependent on the moisture holding capacity of the soil. If the intensive method is used, crops varieties need to be well adjusted to soil moisture stress.The main challenges for the optimisation of spate irrigation system design are (IFAD 2011):

- Improve local diversion structures, ensuring that improvements do not interfere with established water distribution rules

- Avoid damages of the command area by high floods or heavy sedimentation.

- Improve water productivity and soil moisture management.

- Improve field preparations, seed treatment, use of improved seed, early planting and targeted use of agrochemicals.

- Introduce new crops (see also crop selection)

- Improve land and water tenure, issuing individual titles where they do not exist and codifying or reviewing water rights so as to minimise conflicts and accommodate new realities.

- Work on the bigger picture – improve access roads to spate-irrigated areas, general amenities and market facilities (see also integrated water resource management). For example, there is often little equipment and few market facilities that could upgrade production systems. In several spate-irrigated areas in Ethiopia, there is no access to the earth-moving equipment that would make a big difference in developing diversion structures and rehabilitating land and channel systems.

Costs have to be adjusted to the local conditions, project, machinery and material. Furthermore, operation and maintenance have to be considered. In Pakistan for example, costs for material (improved traditional structures) are US$ 10-300 / ha and US$ 10-40 / ha year (NWP 2007). Usually farmers have to be supported by the government and/or an NGO.

A low-cost spate irrigation system has several advantages; it is a simple technology that can be easily maintained, it is less dependent on heavy machinery and important materials and construction / reparation work can be done by farmers themselves (less costly, and it can be done fast and with locally available materials) (FAO 2010).

The main problem for the operation of spate irrigation systems is that stormwater transports a lot of suspended solids and debris. Therefore the climatic conditions and the hydrological characteristics of the wadi need to be known and channels and sedimentation basins have to be flushed and/or cleaned out during the dry season (EMBAYE 2009).

Also the fields and the field bunds have to be maintained regularly (see also the factsheet about field bunds and field trenches). The fields have to be levelled to guarantee an equally water distribution. Moisture conservation (tillage techniques, soil cover, soil amendment or mulching) is as important as water supply and also the soil fertility management has to be considered (read more about this topics in FAO 2010).

The upstream/downstream conflict also affects the standard of living. While a few favoured landowners located at the head of some schemes generate high incomes from commercial-scale farming, most spate irrigators further downstream are poor subsistence farmers, who lack potable water and sanitation, electricity and health care leading to high infant mortality due to malnutrition among children and pregnant women, as well as anaemia, malaria and other health problems (FAO 2010).

If old spate irrigation systems are modernised, its owners/users are often able to increase the water storage volume. In many cases that leads to an upstream/downstream conflict. Therefore, not just the design should be considered, but also social settings and tenure issues; including international water rights (see also the right to water and sanitation) and regional regulations (see also IWRM).

This problem is illustrated by the example of wadi Mawr in Yemen: Here, farmers on the south bank and lower parts of the system have lost access to the water that they could have formerly diverted and have had to rely on the reduced water volumes available in the infrequent, very large floods that pass over the diversion weir. This case shows how an improved diversion system that should have benefited all farmers in a scheme was diverted from its intended role for the benefit of a few (read more in FAO 2010).

| Working Principle | In arid areas, stormwater is diverted from rivers during the rainy season and later used for irrigation. |

| Capacity/Adequacy | Semi-arid and arid areas, which are frequently flooded. |

| Performance | High if floods are frequently and the water rights are respected. |

| Costs | The construction and O&M costs are high |

| Self-help Compatibility | It needs expert design. |

| O&M | It is important to remove sediments and flush sedimentation basins frequently. |

| Reliability | Very reliable if operated and maintained well, but the system is highly dependent of precipitation and the following flood. |

| Main strength | Big areas can be irrigated. |

| Main weakness | Dependent of precipitation and the following flood; Upstream/downstream conflicts. |

Spate irrigation is typical for semi-arid and arid regions such as West Asia, the Middle East (Yemen, Saudi Arabia) or the Horn of Africa. It is only applicable if there are (seasonal) riverbeds (wadis), which are flooded frequently. Farmers in spate systems have developed various cropping strategies to cope with the risks in spate irrigation, e.g. growing local varieties which have a high tolerance to drought. Sorghum, millet, wheat, maize and pulses are the main subsistence crops in spate irrigated areas. Cash crops like cotton or sesame are usually grown only after a staple crop has been harvested and the subsistence needs of farmers have been met (FAO 2010).

Analysis of Spate Irrigation Sedimentation and the Design of Settling Basins

The objective of this thesis study is to analyse the existing sediment control system on spate irrigation scheme, to review and test innovative sediment control and management systems and to recommend as necessary alternative sediment control and management systems and structures.

EMBAYE, T.G. (2009): Analysis of Spate Irrigation Sedimentation and the Design of Settling Basins. Delft: UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education (UNESCO-IHE) URL [Accessed: 08.05.2019]Guidelines on Spate Irrigation

The main objective of this publication is therefore to assist planners and practitioners in designing and managing spate irrigation projects. It covers hydrology, engineering, agronomy, local organisations and rules, wadi basin management and the economics. It is designed to be both a practical guidance document and a source of information and examples based extensively on experience from around the world in areas where spate irrigation is practised.

FAO (2010): Guidelines on Spate Irrigation. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) URL [Accessed: 28.06.2011]Spate Irrigation

Water for Irrigation

Infonet-biovision.org is a web-based information platform offering trainers, extension workers and farmers in East Africa a quick access to up-to-date and locally relevant information in order to optimise their livelihoods in a safe, effective, sustainable and ecologically sound way.

INFONET-BIOVISION (2010): Water for Irrigation. Zürich: Biovision URL [Accessed: 09.04.2019]Smart Water Harvesting Solutions

This booklet on smart water harvesting describes a number of creative solutions in situations where there seems to be no water. It shows practical efforts to "create water", especially in drought prone areas. It does not limit itself to the act of harvesting, but includes capturing water during periods of rain, so that it is available for periods of drought. The book is an effective source of inspiration for local communities, civil engineers, NGOs, research institutes, donors and governments.

NWP (2007): Smart Water Harvesting Solutions . Examples of innovative low-cost technologies for rain, fog, runoff water and groundwater. (= Smart water solutions ). Amsterdam: KIT Publishers URL [Accessed: 12.03.2019] PDFWhat is Spate Irrigation?

A short description how a spate irrigation system works.

SPATE IRRIGATION NETWORK (n.y): What is Spate Irrigation? . Hertogenbosch: Spate Irrigation Network URL [Accessed: 12.07.2010]Analysis of Spate Irrigation Sedimentation and the Design of Settling Basins

The objective of this thesis study is to analyse the existing sediment control system on spate irrigation scheme, to review and test innovative sediment control and management systems and to recommend as necessary alternative sediment control and management systems and structures.

EMBAYE, T.G. (2009): Analysis of Spate Irrigation Sedimentation and the Design of Settling Basins. Delft: UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education (UNESCO-IHE) URL [Accessed: 08.05.2019]Guidelines on Spate Irrigation

The main objective of this publication is therefore to assist planners and practitioners in designing and managing spate irrigation projects. It covers hydrology, engineering, agronomy, local organisations and rules, wadi basin management and the economics. It is designed to be both a practical guidance document and a source of information and examples based extensively on experience from around the world in areas where spate irrigation is practised.

FAO (2010): Guidelines on Spate Irrigation. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) URL [Accessed: 28.06.2011]Smart Water Harvesting Solutions

This booklet on smart water harvesting describes a number of creative solutions in situations where there seems to be no water. It shows practical efforts to "create water", especially in drought prone areas. It does not limit itself to the act of harvesting, but includes capturing water during periods of rain, so that it is available for periods of drought. The book is an effective source of inspiration for local communities, civil engineers, NGOs, research institutes, donors and governments.

NWP (2007): Smart Water Harvesting Solutions . Examples of innovative low-cost technologies for rain, fog, runoff water and groundwater. (= Smart water solutions ). Amsterdam: KIT Publishers URL [Accessed: 12.03.2019] PDFSpate Irrigation, Livelihood Improvement and Adaptation to Climate Variability and Change

Whereas spate irrigation is the ultimate adaptation to climate variability, this document prepared for IFAD is an overview of likely impact of climate change and practical possibilities for livelihood improvement.

STEENBERGEN, F. van VERHEIJEN, O. AARST, S. van HAILE, M.H. (n.y): Spate Irrigation, Livelihood Improvement and Adaptation to Climate Variability and Change. URL [Accessed: 08.05.2019]Irrigation Practice and Policy in the Lowlands of the Horn of Africa

The drought of 2011 and the famine that followed in politically instable Somalia highlighted the vulnerability of the lowlands of the Horn of Africa. It is a story revisited with high frequency – 2000, 2005, and 2008. Climate variability is easily mentioned as the main attributing factor. Clearly it is – but there is also extensive land use change, because of the widespread invasion of invasive species (prosopis in particular) and the decimation of natural wood stands for charcoal production (particularly in Somalia). 2011 was a crisis year – but even in a normal years food insecurity is common. In the Afar lowlands in Ethiopia food aid has become part of the livelihoods, with most of the people dependent on it – including reportedly middle class families. There is a growing realization that water resource development – appropriate to the context – has to have a place in addressing food insecurity in the Horn of Africa. This paper focuses on irrigation policy and practice in the arid lowlands of the Horn that have been hit hardest and most frequent in the drought episodes

ALEMEHAYU, T. DEMISSIE, A. LANGAN, S. EVERS, J. (2011): Irrigation Practice and Policy in the Lowlands of the Horn of Africa. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) URL [Accessed: 26.03.2012]Dodota Spate Irrigation System Ethiopia

This case study focuses on the water management of the Dodota spate irrigation system, the first large scale spate irrigation system in Ethiopia. This system in the Oromia state has been recently designed and constructed to establish food-self sufficiency in an area chronically affected by food deficits and supported by food aid for over 25 years. The following main research question guided this study: How is water management taking place in the new Dodota spate irrigation system and what are the impacts and effects for irrigation, soil conservation practices, and production?

HAM, J.P. van den (2008): Dodota Spate Irrigation System Ethiopia. A case study of Spate Irrigation Management and Livelihood options . Wageningen: Wageningen University URL [Accessed: 08.05.2019]Eritrea - Projects, Programmes, Publications and Videos

Water is precious in Eritrea, where farmers have to cope with droughts and crop failures. With support from the government and an IFAD-funded project, farmers and herders are expanding spate irrigation, an ancient form of water management. By harnessing floodwaters and collecting run-off, farmers can provide enough water for the crop season. Now some farmers can obtain yields that are six times what they used to be.

http://www.spate-irrigation.org/

This website is all about spate irrigation; Many useful information such as guidelines, links, library and spate irrigation network partners.