The Vertical Garden is a stackable planter made for indoor and outdoor use. Also called plant wall, green wall and bio wall, this is a light framed, mostly self –supporting plant community where the necessary water, light and plant food are provided by a highly automatised system. The system is based on the principles of hydroponics where the plants are rooted in a porous material soaked in fertilizer instead of soil. When adapting its construction to improve the filtration capacity, this can be used also as greywater treatment, permitting to reuse the treated water.

| The contents of this factsheet are results of the Indo-European Project NaWaTech- “Natural Water Systems and Treatment Technologies to cope with Water Shortages in Urbanised Areas in India”, co-financed by the EC and the DST – India. |

Design of a Vertical Garden

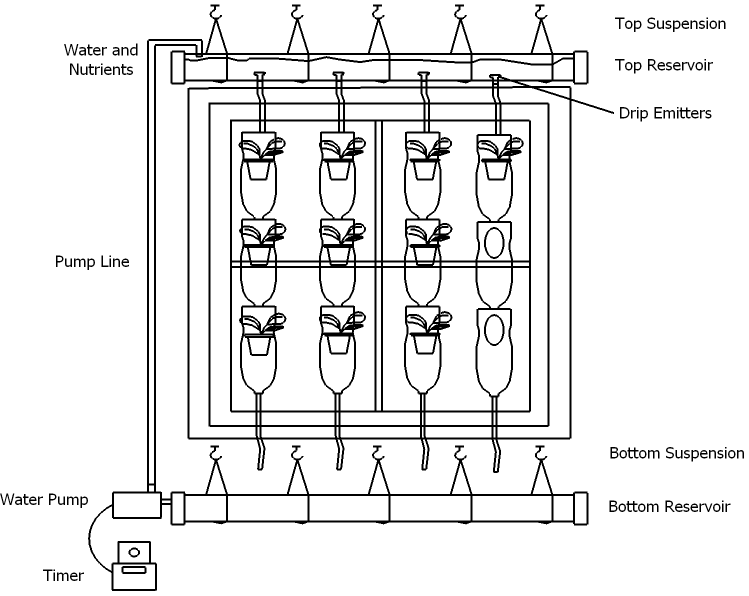

The design of vertical garden depends on the available material, space and local preferences as well as on the creativity and imagination of the users. There are very simple designs like tray models similar to nursery flats, where rectangular, plastic trays are divided into planting cells — all slanted at a 30-degree angle, with bottom holes that promote drainage and aeration. Each tray comes with a bracket for mounting. Complicated structures like green wall can be also there where the structure itself is a 10 mm-thick humidity-proof plastic panel fitted on a stainless metal frame, which is covered in a special, rot-free, absorbent synthetic felt in layers. This felt serves as pockets for planting. The entire width of the structure is 4-20 cm, with the larger for greywater treatments.

The supporting frame includes a water-tank and an automatised drip irrigation system. A properly adapted green wall can receive greywater instead of normal water, ensuring a good level of treatment; greywater have to be pre-treated (degreaser and a pre-filter are suggested to avoid obstruction of the drip irrigation system and of the vertical filters). There are very few applications in the world with treatment purpose; even these experiences are successful and interesting, currently it is difficult to list precise construction principles: generally, they use different panel types and various filling material (LECA and other lightweight granular material seem the most adaptable).

The selection of the plants is a technical criterion of utmost importance because determines the texture, colour-combination, shape variety and life span of the wall and in case of treatment also the removal efficiency The loading often happens on two panels in series. A pilot system recently developed in Germany (ROUSSEAU & BAUMER 2013), with a hydraulic loading rate of 35 L/ m2 of vertical wall (2 m2/PE), the unit shows removal of 96% for COD, 91% for N, 67% of P, 97% of foam, whereas the disinfection is limited to 2 log.

Vertical gardens require more maintenance than gardens in traditional horizontal plane. Fertilisation and watering (usually using nutrients enriched water) should be automated to ensure that the needed ingredients are evenly -and regularly- distributed. In this sense the use of the vertical wall as greywater treatment could be attractive, considering that the greywater are normally produced every day and they could substitute the irrigation needs.

Cost depends on design chosen. A simple tray model will cost up to a maximum of 100€, which includes the costs of tray, wire mesh and fertiliser. However, big scale vertical gardening projects can be really expensive; the species and the demands of the plants as well as the automated systems used are greatly affecting the cost of the project. ROUSSEAU & BAUMER (2013) have estimated the cost of a 4 PE greywater treatment by green wall in 2,600 € (650 €/PE) including disinfection (excluding labour).

Several vertical gardens are growing in many cities around the world, but the examples of green walls used for greywater treatment at large scale are very limited. Promoters of the green wall mention in publications that greywater or recycled greywater is a possible irrigation source for the vegetation system (WEINMASTER 2009). There are some examples of green wall installations, which use recycled greywater, such as “The Gauge” in Melbourne, Australia built by The Greenwall Company (HOPKINS & GOODWIN 2011).

A relevant case is constituted by the 2,500 m2 vertical garden at the Tabacalera Space in Tarragona (Spain): completed in December 2011, the green wall is made by Babylon type modular pieces 50 x 100 cm and 14 cm thick substrate and it constitutes in this case the tertiary treatment after a horizontal flow system. The process is developed and patented by Vivers Ter-Asepma as proven greywater treatment by biofiltration using the architectural element of the vegetable walls, and permits the regeneration of greywater from shower and sink for different uses such as irrigation of green areas or supply the toilets.

A pilot vertical filter wall (175 cm depth) was constructed in Ås, Norway and dosed with domestic greywater for a period of three months. Despite a daily dosing rate of nearly 1000 l/m2 the system achieved average reduction rates of over 95%, 80%, 90%, 30%, and 69% for BOD5, COD, TSS, total nitrogen, and total phosphorus, respectively, as well as approximately two log unit reduction of E. coli. (SVETE 2012)

Another demonstrative system is built at Gammelgarn on the Island Gotland, eastern Sweden; the green wall shows good removal of pollutants (95% P, 75% COD, 50% N, 99.5% E. coli) and respects the reuse limits. The dimensions of the wall are 2.40 x 1.55 height x 0.2 m thick and the filter material is gravel (average diameter 1 cm), placed on the backside where greywater is put in, whereas on the front side there are 18 compartments where plants are growing (BUSSY 2009)

No experiences of green wall for greywater treatment are documented in India; the following examples are successful experiences of vertical garden in the country.

Antilia, Mumbai is designed as the largest and tallest living wall in the world - a seamless, vertical garden that encompasses all walls of the building climbing to the 40th floor. Chicago-based Perkins+Will designed the 24-story tower for business tycoon Mukesh Ambani. Antilia features a band of vertical and horizontal gardens that demarcates the tower’s different programme elements. In addition to signalling different space uses and providing privacy, these “vertical gardens” help to shade the building and reduce the urban heat island effect. The cost of the building is reported to be 1 billion dollars (MATHEWS 2007).

One of the other examples in India is the Qualcomm Green Wall, which is the 1st indoor green wall project in Bangalore. It is a model indoor green wall project done by ZTC international Landscaping solutions Pvt Ltd. The Qualcomm Green Wall, as conceived by the Architect of the building, is located facing the cafeteria. The wall is aimed at providing aesthetically pleasing appearance to the plain wall and also to improve the indoor air quality. It was installed in 2010 with a wall size of 51.6 m2.

For more information please visit: Vertical Gardens

| The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme ([FP7/2007-2013]) under Grant Agreement N° [308336] and the Department of Science and Technology of the Government of India DS.O DST/IMRCD/NaWaTech/ 2012/(G). |

The Vertical Garden City: Towards a New Urban Topology

Article on vertical gardens in cities.

ABEL, C. (2010): The Vertical Garden City: Towards a New Urban Topology. In: Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) Journal Issue II: , 20-30. URL [Accessed: 10.07.2013]An Innovative Way to Treat Wastewater

The aim of this study is to present an innovative way of treating wastewater in dry areas in the countryside, and to describe its efficiency, its competitiveness and its advantages. The household scale treatment facility at Gammelgarn on the island Gotland, eastern Sweden, associates a biological greywater treatment to reuse of treated water.

BUSSY, E. (2009): An Innovative Way to Treat Wastewater. Strasbourg & Uppsala: Engees (Ecole national de Genie de l'Eau et de l'Environment de Strassbourg) and Uppsala University URL [Accessed: 10.07.2013]Vertiscaping

This document aims to communicate the advantages and scientific workings of living walls and green screens. The different types of walls, how they are constructed, their biological components and effects on their environments are the major points of interest. A few case studies aim to look into some of the green wall methods that have been put to use around the world. Similar approaches of vertical planting are also looked at, including retaining wall systems and methods of adding green space to skyscrapers.

HEDBERG, H.F. (2008): Vertiscaping. A Comprehensive Guide to Living Walls, Green Screens and Related Technologies. Davis: University of California URL [Accessed: 10.07.2013]Living Architecture

Extensively illustrated with photographs and drawings, Living Architecture highlights the most exciting green roof and living wall projects in Australia and New Zealand within an international context.

HOPKINS, G. GOODWIN, C. (2011): Living Architecture. Green Roofs and Walls. Collingwood: CSIRO PublishingPatrick Blanc's Vertical Gardens

Patrick Blanc’s Vertical Garden System, known as Le Mur Vegetal in French, allows both plants and buildings to live in harmony with one another. The botanist cum vertical landscape designer is probably best know for his gorgeous living wall on the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris.

LEE, E. (2011): Patrick Blanc's Vertical Gardens. El Segundo: Inhabitat URL [Accessed: 12.08.2013]Perkins + Will Debunks Antilia Myths

Vegetated Greywater Treatment Walls: Design Modifications for Intermittent Media Filters

Are Green Walls Really as "Green" as They Look?

This article aims to clarify what green walls are, going into detail about the various technologies available; the pros and cons of each; and the ecological, social, and economic benefits of these living works of art.

WEINMASTER, M. (2009): Are Green Walls Really as "Green" as They Look?. An Introduction to the Various Technologies and Ecological Benefits of Green Walls. In: Journal of Green Building: Volume 4 , 3-18. URL [Accessed: 25.03.2015]Compendium of Natural Water Systems and Treatment Technologies to cope with Water Shortages in Urbanised Areas in India

The Compendium of NaWaTech Technologies presents appropriate water and wastewater technologies that could enable the sustainable water management in Indian cities. It is intended as a reference for water professionals in charge of planning, designing and implementing sustainable water systems in the Indian urban scenario, based on a decentralised approach.

BARRETO DILLON, L. ; DOYLE, L. ; LANGERGRABER, G. ; SATISH, S. ; POPHALI, G. (2013): Compendium of Natural Water Systems and Treatment Technologies to cope with Water Shortages in Urbanised Areas in India. Berlin: EPUBLI GMBH URL [Accessed: 11.12.2015]http://www.nawatech.net/

This is the official webpage of the NaWaTech Collaborative Project, containing all key information related to the different case studies, activities and results of the project.