This case study supports and illustrates the theoretic factsheet "Public-Private Partnerships for safe water businesses" with practical insights.

'The health of the people is our mandate'

Water utilities in Ethiopia have been involved in a pilot project to promote and sell household water filters, in a public private partnership (PPP) construct with suppliers of household water filters (Sawyer and Tulip) and Aqua for All as facilitator. In Finote Selam, a town of 77,000 inhabitants, the mayor and other local government bodies actively endorse this approach by promoting it in different platforms and meetings. The motivation of the water utility manager and his board to engage in the PPP approach is that it helps them achieve their mission to supply safe drinking water to all households in the respective service area. In a fast-growing town like Finote Selam, households who are demanding access to drinking water are given an intermediate solution: the utility can provide them with a water filter of their choice, so they have access to safe water at point of use. This pilot has demonstrated that water utilities as distribution channel and sales agent can potentially lead to a huge market penetration for household water filters and safe water accordingly.

Can water utilities ensure access to safe water at point of use for all households by promoting and selling household water treatment solution (HWTS) products? During a session at Stockholm International Water Week in 2015, a representative of the Ethiopian Ministry of Water, Energy and Irrigation invited Aqua for All to pilot such approach in Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, still more than 90% of child deaths are due to preventable diseases like diarrhoea. The country’s policy is thus to reach universal access to safe drinking water at point of use by 2020 (Growth and Transformation Plan II (GTP2)). The government wants (and needs) to test innovative solutions in order to reach this target. It is in this setting that HWTS can serve as an important measure to make drinking water safe.

The Ministry invited Aqua for All to present the ideas on ‘New pathways to scale HWTS’ at a regional HWTS workshop in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia mutually organized by the government and WHO from 3-5 May 2016. After this workshop Aqua for All decided to start the project with a feasibility study to answer the following questions:

- Will promotion and sales of HWTS constitute a sustainable business model for water utilities?

- Can this distribution model also provide HWTS to low income households?

- Will this approach lead to correct and continuous use of HWTS?

Four out of five utilities who participated in the feasibility study showed interest to pilot the approach, especially the utilities where a water quality assessment recently showed bad results regarding the presence of e-coli and other bacteria.

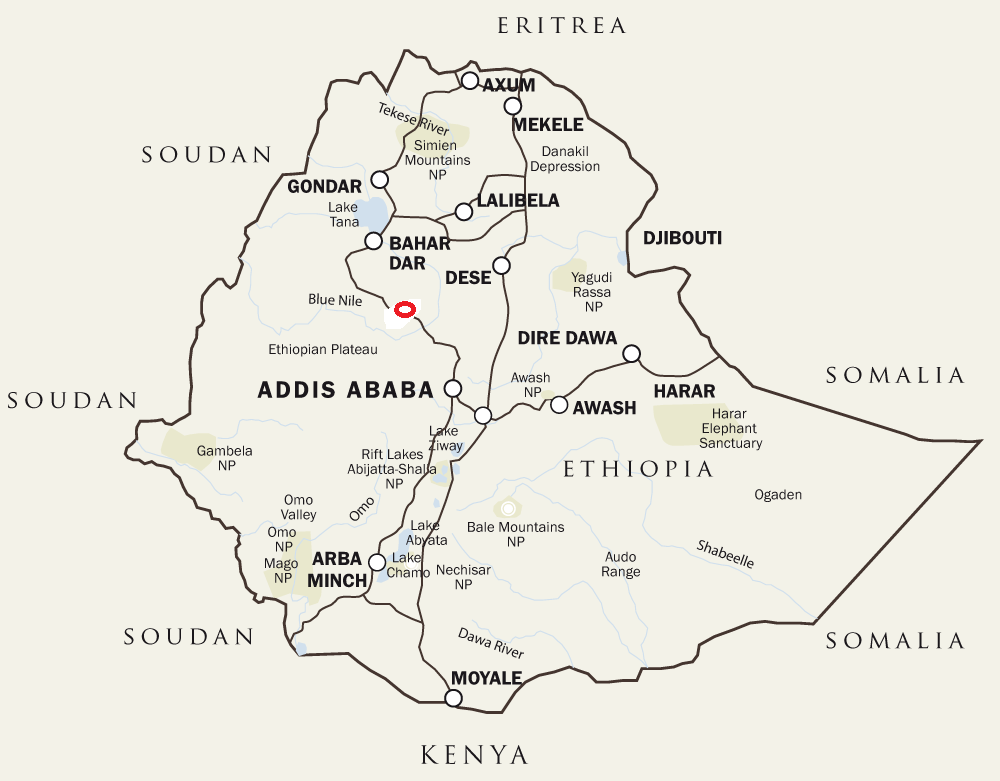

One utility would be interested if the technologies would remove fluoride, which is a huge problem in large part of the country (Rift Valley). However, at the moment this pilot started no low-cost solutions were available to remove fluoride or other chemicals.. In November 2016, a one-year pilot was started in the fast growing town of Finote Selam in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. The local water utility decided to promote physical filters only as chemical treatment products are frequently distributed in emergency situations and do not lead, in their experience, to sustained use. Besides the technology choice the utility manager put three conditions when initiating the pilot:

- No free gifts (no free distribution of filters to customers)

- Support from all local decision makers

- After-sales have to be part of the service package offered.

Three filter options were selected (CHEKOL, 2016), all available in the country: Sawyer, Tulip Siphon and Tulip Table Top:

In November 2016, after introducing and demonstrating the HWTS products, tri-partite agreements were signed between the water utility of Finote Selam, private sector providers of filters and Aqua for All. For the one-year duration of the pilot, Aqua for All paid a small topping up of the salary of 8 staff of the utility to incentivize staff promoting HWTS and collect data accordingly. The suppliers consigned a number of products to the utility office, to be paid after the utility would receive payment of the end users. During one year, utility staff actively promoted and distributed the filters and offered after-sales services whenever customers called. Broken filters were replaced and problems of non-functionality were solved by a demonstration on the correct use and maintenance of the filters. To cover these service costs, the utility staff charged 20% on top of the wholesale price. After one year of piloting the approach, the utility manager calculated that the utility will break even at a sales volume of 5,000 filters per year. In November 2017, 500 filters were sold and another 2,000 just arrived (with half a year of delay due to different import challenges). Until the end of 2017 over 2,500 filters were sold and the different Zonal Water Heads involved planned and ordered together 30,000 filters to be sold in 2018 only. Reaching this point implicated also a couple of challenges that had to be overcome:

Admitting that water quality is an issue

For incepting such PPP pilot project the first hurdle to overcome is that utilities admit that their drinking water has a quality problem. This demands leadership and political will to publicly disclose water quality issues. Accordingly the replicability of the approach depends largely on the policies in place and the authorities’ and utilities’ will to implement those.

Scaling up 1: commercial marketing by the utility

Commercial marketing through advertisements is not widely practiced in Ethiopia. Private sector is generally not trusted in their messages and the government is seen as more reliable in this regard. Monitoring during the pilot phase showed that promotion is best done by word-of-mouth and making use of community leaders and social gatherings like church meetings and funerals. The utility uses small posters to advertise the filters including telephone numbers for more information and to place purchase orders. Towards the end of the one year pilot, the utility started preparing radio messages to reach out to a wider public. The utility is very much convinced that after-sales services are key to reach overall customer satisfaction, as customers are also clients for the supply of water. At the same time the utility is aware that offering reliable after-sales services will be a challenge when sales volumes increase substantially.

Scaling up 2: local water authorities adopt the approach and demand filters to cover the whole population in West Gojjam (2,400,000 people) within two years.

During a water quality meeting of the zone surrounding Finote Selam in December 2017, the Water Bureau of the Zone decided to adopt the HWTS approach in the whole zone. Finote Selam Utility shall serve as warehouse having a 5% margin on the wholesale prices, the water authorities of the surrounding small towns and rural communities shall serve as local distribution and training centres having 6% margin and local civil servants as sales force to promote the filters to end users in their own time (with a margin of 9%). This way, the Water Bureau wants to fulfil its task to provide safe water to all households.

Securing the local supply chain and way forward

Ethiopia is a land-locked country with a difficult foreign exchange scheme, which makes imports quite challenging. In October 2017, the government devaluated the local currency to stimulate local production in order to substitute imports. Hence also local production of filters becomes very interesting now as there seems to be an enormous demand for filters in the future. In 2018, two different companies will start with local production of Table Top filters in Ethiopia. The government taxing system encourages local production by applying a low tariff on inputs as compared to finished products. For imported filters like the Sawyer, the new government policy will be asking whether the imported filters are able to compete with the locally produced filters.

- The water utility must be committed to deliver safe water to all people, especially those with low incomes and living in rural settings. This will drive the search for business models to make filters available for all through new payment systems, cross subsidies or other innovative mechanisms.

- To create common ground for the pursued approach, the utility manager started with a discussion inviting all local decision makers to gather with the board and the staff of the utility. During the meeting water quality in the concerned area as well as the feasibility of potential Point-of-Use solutions were on the agenda. Pros and cons were discussed and the utility received endorsement for pursuing the approach with the support of the concerned stakeholders. Such procedure was reported to be key for successfully initiating any novel approach.

- The utility staff members started buying a filter for their own household as a first step to test it themselves and then demonstrate and promote the products to their peers and in their communities. This helped increasing the trustworthiness of the products.

- Policy advocacy work was done towards water authorities in the region who endorsed the HWTS approach and expressed their interest to adopt it to promote the approach at national/federal level. This led to scaling up the approach in the whole region, targeting 2,400,000 people.

- Aqua for All’s local consultant played the important role of a facilitator during the pilot process, offering expertise on the water quality issue and providing support for calculating costs and revenues for the utility. In such case a facilitator should be trusted by the utility in order to perform an advisory role on water quality issues and utility management and also have a neutral but trustworthy position towards suppliers to support the launch of such project.

- Different payment modalities were offered: upfront payment, or in instalments (with an up to four months repayment period). These instruments turned out to increase affordability substantially. For this pilot the private sector was willing to take the risk of pre-financing the filters in stock; however, when volumes will increase the risk allocation (non-payment, cash flow problems) will have to be re-discussed between the partners.

- Monitoring started with a baseline survey with the first 100 households, followed up by a mid-term review after 6 months. The monitoring of the project was crucial for identifying challenges and helped adjusting strategy and implementation of the second part of the project.

- Utilities may not reach the most remote areas yet, but they can become a distribution centre for surrounding communities. As an example: End of 2017, the Zonal Head of West Goijam ordered 20,000 filters for the 13 rural woredas (i.e. districts) around the town of Finote Selam. To attract the involved organisations to deliver the filters margins are key to incentivize promotion and delivery.

- The head of the Regional Water Bureau of Amhara Region invited suppliers of filters to actively promote their products in the region, because he is convinced that physical filtration can help to prevent the recurring outbreaks of acute watery diarrhoea. At the same time, the bureau is revising the legislation at national level to make sure utilities can legally purchase and resell filters.

- Transparency on the current water quality helps to build trust as transparency is highly valued in Ethiopia. If people know from their health centre that they are suffering from waterborne diseases, they will immediately link this to their source of drinking water leading to an increased likeliness to purchase and use water filters to have safe water at home.

- The success of the outlined PPP approach depends on the social interest of the government as well as on the business case for all partners involved in the supply chain: suppliers, utilities and sales force. Since water companies in Ethiopia are stimulated to base their operations on a viable business model, it is economically interesting for them to serve clients with water filters as intermediate or additional service.

- The leadership role of the utility, the mayor and other local decision makers involved in such a PPP is a key success factor to sustain the approach and to scale it horizontally (to other utilities) and vertically (to bring about systemic change, like policy change towards water quality at PoU, exemption of import tax etc.).

- Household water treatment can be promoted as an ‘intermediate’ service for the unserved communities in order to increase acceptability and aspiration.

- A public private partnership approach needs to be formalized through a contractual agreement between the involved parties. Having clear roles and responsibilities for each partner including a good governance structure and profit and risk sharing mechanisms will increase trust and transparency between the partners and willingness to make the project work sustainably.

- Utility staff involved in the PPP should be skilled in promotion, sales and aftersales.

- It is important to give utilities and their customers, a choice of options but neither too many, all of good quality, tested and approved by the national and local authorities.

- Start with the best performing utility to create a centre of excellence which can train others through exposure visits and experience sharing.

Desk research of Household Water Treatment and safe storage, (HWTS) promotion and distribution through Water Utilities in Ethiopia

Aqua for All NGO

Aqua for All is a non-profit organization established in 2002 by the Dutch water sector. Aqua for All is a well-known source of expertise on water, sanitation and hygiene-related challenges, offering a broad range of services to the public and private sector. With its business-like, efficient and result-oriented approach, the organization inspires and supports its stakeholders to help the world’s Base of the Pyramid gain sustainable access to safe water and adequate sanitation.

PPPLab

The PPPLab is an action research and joint learning and support initiative to learn about the relevance and effectiveness of PPPs. Starting point is the Dutch government supported public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the food and water domains in developing countries. Its mission is to extract and co-create knowledge and methodological lessons from and on PPPs that can be used to improve both implementation and policy.